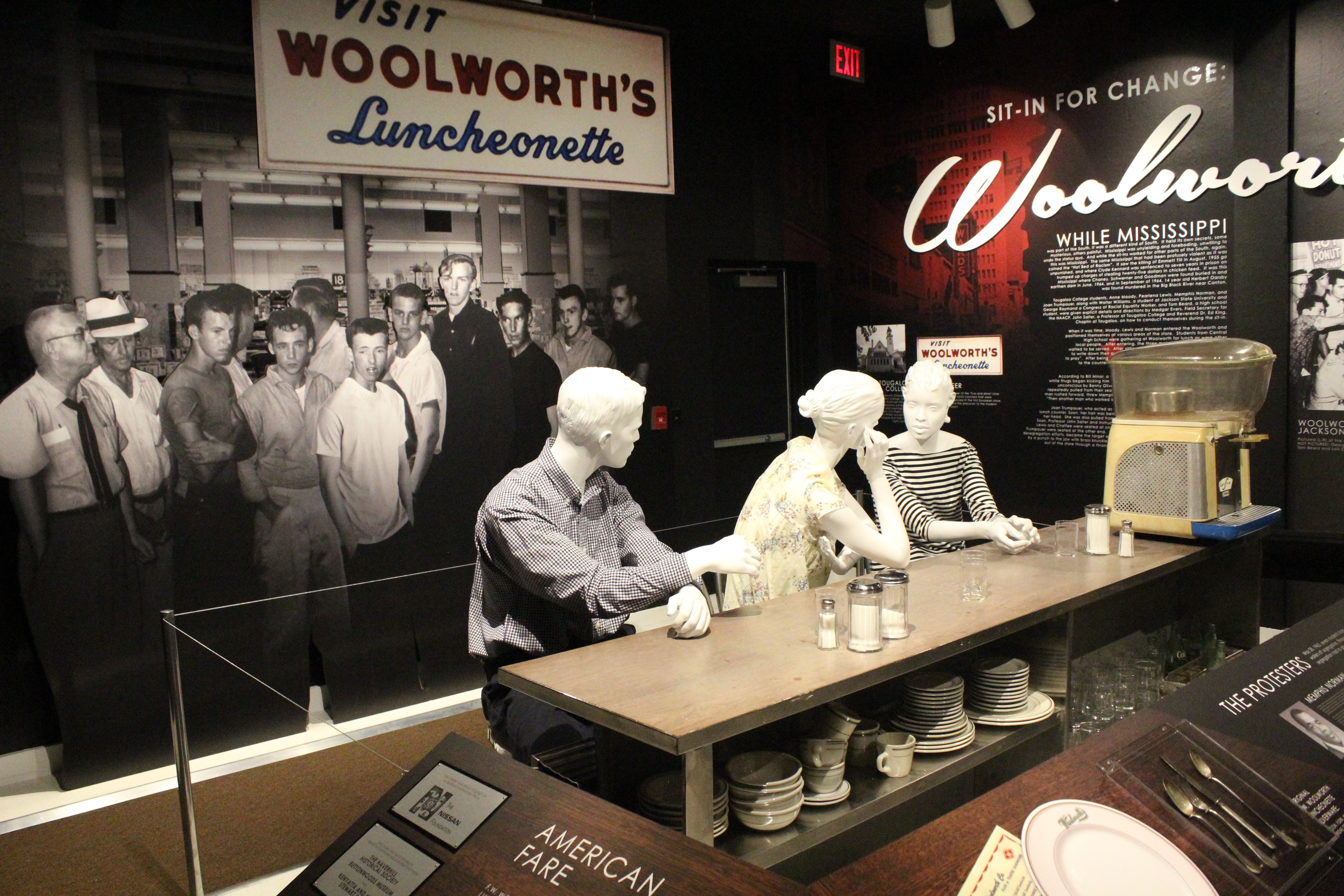

Photo above by Chauncey Nettles: The “Woolworth’s Sit-In for Change” Exhibit opened at Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center this summer.

Rev. Edwin King came to the Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center in downtown Jackson on June 14 ready to educate the audience there during a conversation about the “Woolworth’s Sit-In for Change” Exhibit.

The 80-year-old white Civil Rights Movement veteran quoted Medgar Evers—”Any change is the start”—as people in the packed atrium nibbled on Broad Street Bakery sandwiches and salad. King then dove into his account of the sit-in, where he was a spotter. As the diverse mix of young activists violated Mississippi law by sitting at the lunch counter at Woolworth’s, on the site of the present-day One Jackson Place building including a Wasabi restaurant, the then-Tougaloo College chaplain was tasked with being a lookout. He told the protesters what the police were doing, he called NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers every 15 minutes on a pay phone to give updates on what he saw, including any violence.

King and Evers, who later was killed for fighting for civil rights in Mississippi, were good friends. In fact, Evers treated King like a brother. Evers had pulled King into the action, just as the young reverend hoped he would. They worked closely together as advocates for change until Evers’ murder, which happened only a few weeks after the sit-in at Woolworth’s.

Rev. King brought news clippings, books and slides to show the audience what the terrifying three hours of the sit-in were like. The young people were at Woolworth’s to demand equal rights to accommodations and public services for black Mississippians who were living under strict Jim Crow laws that did not allow integration of any kind.

Hurled to the Floor

King described three black Tougaloo students—Anne Moody, 22; Pearlena Lewis, 20; and Memphis Norman, 20—entering the store. “We knew that you could hardly be accused of trespassing if you had already made a purchase in the store,” he said. So the young activists made their purchases and sat down at the “whites only” lunch counter.

“The official white viewpoint was that trouble did not start when white hoodlums violently attacked the demonstrators, but the trouble started when blacks peacefully sat down at the lunch counter,” King said at Smith Robertson. He remembers talking to Kenneth Toler, a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, who said, “This can’t stay this peaceful for long. This is Jackson.”

”Memphis was hurled to the floor,” King continues. “The crowd shrieked. Both girls were knocked to the floor, quickly got back up to their seats at the counter. Memphis Norman just lay on the floor, blood pouring from his mouth and nostrils. … The shouting of the mob died down to a low giggle, a kind of communal snarl. The only other sound was the low moaning from the body on the floor, … All this took place in the glare of numerous floodlights from television camera crews… This went on for several hours and became national TV and live radio.”

King described a “beautiful blonde belle” walking up to the counter and picking up a plastic bottle of mustard, then making a “brilliant stain” on Moody’s black hair then on Lewis’ head. “Next came three teenage white boys,” King said. “They grabbed up all the nearby food containers from the counter and showered the black women with salt, pepper and sugar. … I whispered to the women at the counter, ‘Medgar says it’s OK if you want to leave,’ and they said, ‘No. We will stay ’til the end, whatever the end may be.'”

Black attorney Constance Slaughter-Harvey, now 71, appeared alongside King at Smith Robertson, which was Jackson’s first high school for African Americans when it opened in 1894. Slaughter-Harvey was with Medgar Evers at the NAACP office during the sit-in. She was partially tasked with keeping Evers from leaving to join the demonstration, as he was specially instructed not to join in a protest. At the luncheon, she explained how, while she respected Rev. King at that time, she did not believe that a non-violent approach would make a change. But looking back now, she said realizes that change would only have happened with the non-violent approach of the Civil Rights Movement, which was modeled on Ghandi’s principles.

Black attorney Constance Slaughter-Harvey, now 71, appeared alongside King at Smith Robertson, which was Jackson’s first high school for African Americans when it opened in 1894. Slaughter-Harvey was with Medgar Evers at the NAACP office during the sit-in. She was partially tasked with keeping Evers from leaving to join the demonstration, as he was specially instructed not to join in a protest. At the luncheon, she explained how, while she respected Rev. King at that time, she did not believe that a non-violent approach would make a change. But looking back now, she said realizes that change would only have happened with the non-violent approach of the Civil Rights Movement, which was modeled on Ghandi’s principles.

“I agree that, had it not been because of the Ghandi and King approach, change would obviously not have taken place,” Slaughter-Harvey said at the museum. “For those individuals who are brave enough, like my cousin Norman, to sit and let somebody physically abuse them, I have the utmost respect. I see now the value of that, especially when people are trying to get people to fight. It’s like the advice we give young people about bullies: if a bully can really make you mad, then he’s won.”

Slaughter-Harvey also thanked King for his service as an ally to a cause that was dangerous and violent for activists of any race—he still has a scar on his face from when a white man drove into the car he and John Salter were in after a meeting with U.S. Justice Department officials. “Let me publicly thank Ed,” she said. “Every time I look at him, I look at his scar, and I get mad. Even with the physical scar, and I know there are many mental and emotional scars, he’s still out there fighting. … Those of you young folks who have no idea what it was like, he brought you to the counter, and I want to thank him for that.”

Facing Injury and Possible Death

After the talk, the museum opened the upstairs door to the Woolworth exhibit, with an entrance modeled like the front porch of a house. Pushing open the door, visitors entered into an open space with artifacts, informational signs, paintings on the wall, and more. One sign described Evers’ experience in the military. Another sign was an American flag, painted with quotes advocating for voting rights and desegregation.

Around a turn, an area was set up as a model lunch counter with mannequins of three people sitting on the stools.The three represented “The Protesters,” a sign beneath them read. A crowd of leering whites with a Woolworth’s sign above them appeared on the wall behind the counter. One of the original Woolworth’s stools is in a display case next to a wall painted with two words: “Brutal Attack.”

Every sign, illustration, and informational display reiterated exactly what Ed King and Constance Slaughter-Harvey spoke of at the luncheon—the protesters, even facing injury and possible death, did not back down from their demonstration as they faced a brutal attack that lasted for hours, including descriptions of what happened and pictures of the sit-in.

Dialogue Jackson, a nonprofit working to improve race relations in the capital city (and the nonprofit sponsor of the Mississippi Youth Media Project), hosted the luncheon. The Nissan Corp. sponsored the exhibit.