by Asia Mangum, Kenytta Brown and Makallen Kelley

Maati Joan Prim greets visitors to Marshall’s Music & Bookstore on Farish Street with a warm, enthusiastic hug, making them feel welcome from the start. On this day, her hair is wrapped in a yellow African head wrap, and she wears a matching shirt and an orange dashiki skirt, complemented with a septum ring and large red heart-shaped earnings. She beams with a wide grin, bearing all her teeth to match her vibrant personality. The sun shines through the window, adding an extra glow to her cocoa-brown complexion.

Every morning, Prim starts her day off communing with her ancestors and meditating. Like most small business owners, she has no time to spare, filling every moment by answering phone calls, finishing computer work and organizing her office.

There is no time to waste.

Prim is an example of a longtime business owner on Farish Street—one of the few left in Jackson’s historic black business district that has suffered from flight and decay in recent decades. Marshall’s, which specializes in educational and history books, has been in her family for generations, and Prim became current owner and operator since her aunt passed it down to her.

Not only a business owner, Prim is an activist against mistreatment of prisoners and has an African belly-dancing studio. The dance is good for healing and a stress reliever, Prim says. She has helped women who are pregnant and with their deliveries, along with women who are going through the “changes of life,” hip problems, and other ailments.

“The studio helps with the physical healing, and the bookstore takes care of the spiritual, educational and mental healing,” the black business owner told the Youth Media Project in her store.

‘The Black Mecca of Jackson’

Today, the Farish Street district is neglected with many worn-down buildings and forgotten blocks with a small number of active businesses on it. You would never think that this impoverished street was once a booming hot spot for Mississippi if you did not know it already. Before and during the 1960s, black-owned business, commerce and nightlife dominated the street. Much of the southern blues and soul recording industry was headquartered on the strip.

Of course, just like historic black business districts from Beale Street in Memphis, Tenn., to Parrish Street in Durham, N.C., one reason for Farish’s heavy commerce was Jim Crow segregation. Because state law then restricted where African Americans could spend their money and dine, areas such as Farish became centers of shopping, eating out and entertainment for them. Farish Street was a safe place they went for service without being discriminated against.

Many people called Farish the “Black Mecca of Jackson” over the years. From some of the top soul-food restaurants in the South to record stores with the best soul music, Farish Street was the perfect place for a night out on the town. You could grab a bite at Peaches Café, dance at the Crystal Palace and then catch a show at the renowned Alamo theater.

But as times changed—and the federal government outlawed segregation laws, opening up more options for black people—the clock began to wind down on Farish Street. Businesses closed, people moved away, and it was no longer as popular as it used to be. But for some people, Farish holds a place in their hearts. It’s still relevant as ever and is only slowing down, not shutting down.

Prim is one of those people. Supporting black-owned businesses is one way to bring healing to the Jackson community, Prim says of the capital city, which is now 80 percent African American.

Being in the business for a long time and seeing her family own this bookstore, Prim has watched the changes the black community has gone through. That makes her determined to support black-owned businesses. “It is absolutely essential for every black person to take upon themselves the responsibility of healing our community,” Prim says.

Even though Farish isn’t as busy as it used to be, there is still a strong community base willing to look out for each other. “Sometimes when I come in early at 3 o’clock in the morning because I have a lot of work to do, they’ll stand outside to make sure nothing goes wrong,” Prim says of neighbors.

Another example, Prim added, was when a woman tripped and fell in the street. They picked her up and carried the woman into the bookstore where Prim had a first-aid kit. Prim put bandages on her and made sure she was OK before they walked her back outside.

“Well that’s Farish Street. However, that should be anywhere any black person is,” she says.

Of ‘Redlining’ and Economic Control

As a black entrepreneur in a tough climate, Prim is a supporter of Respect Our Black Dollars an organization that supports and promotes quality black-owned businesses. Its president and founder is Stanley Wesley.

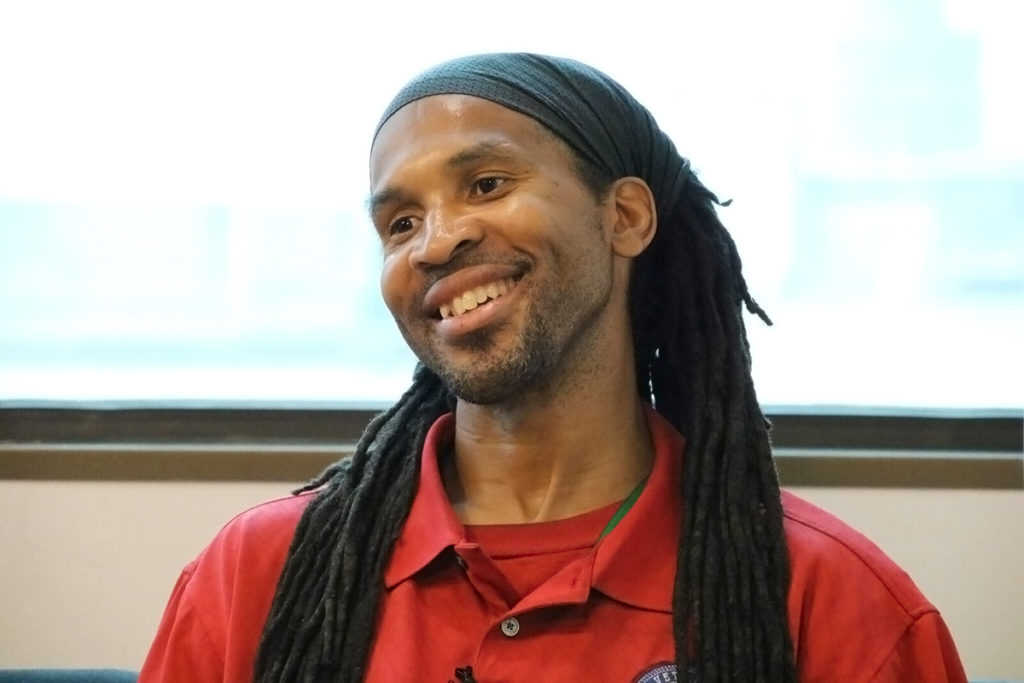

David Mosley, who likes to go by Mr. D-Meezy, has been a member since the beginning of the group in 2012. He has long believed in the cause of spending money with black-owned businesses. “No matter where I am, what I’m doing and what I’m not doing, I will always be a part of this for the rest of my life,” he said in an interview at the Youth Media Project.

Mosley said it is important for black-owned businesses is to have control of the economics of their community. “When you do not control the economics of your own community, then that means the control is in the hands of other people,” he said.

The three primary objectives of Respect Our Black Dollars are: support quality black-owned businesses; promote black economic community-control models; and spur development in black business infrastructure.

ROBD leaders not only supports black-owned businesses, but they also do “buy-ins”—supporting certain businesses in large groups at coordinated times. They speak to owners about how to improve their businesses based on complaints or affirmation from the community, and screen films including “Hidden Colors,” “Out of Darkness” and “Black Wall Street.”

Since ROBD formed, it has added a radio show and more members and gained a younger audience, Mosley says. Many of the members have become entrepreneurs themselves as a result of joining the organization.

Mosley said black-owned businesses haven’t been the most successful because they’ve been held back in a game of monopoly. “Black people had to compete with people who had longer relationships with banks and the community, while not having what it takes like those of mass wealth,” he told YMP.

African Americans have been blocked from achieving wealth and access to resources that would help them start and own businesses. Unfair lending practices, such as “redlining”—drawing a line through the names of black people to keep them getting a home or business loan—is a long-time discriminatory practice that was widespread through the 1970s. The practice kept black families from building and then inheriting the credit and access to increasing amounts of capital that still block many entrepreneurs of color from building strong businesses.

In fact, the U.S. Department of Justice fined Tupelo, Miss.-based BancorpSouth $10.6 million in 2016 for redlining minority residents in the Memphis area out of loans and charging people of color higher interest rates when they did get loans. The bank also refused to build branches in many majority-minority neighborhoods. The discriminatory practices occurred from at least 2011 through 2013, the DOJ said.

The Associated Press explained “redlining” in its 2016 story about the BancorpSouth fine: “The term stems from a time when banks would outline minority neighborhoods in red marker as places where loans were to be denied. The practice cut off entire neighborhoods to capital, and many housing experts blame redlining for why large minority neighborhoods decayed and slipped into poverty in the second half of the 20th century. It also cut off minorities from home ownership, one source of wealth generation for the U.S. middle class.”

That blocked wealth generation based on skin color makes it much more difficult for black entrepreneurs to have the resources to launch businesses and succeed.

Still, from 2007 to 2012, black business ownership in Mississippi increased 60.8 percent, the U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy reports. It’s those businesses Respect Our Black Dollars wants to get people to support.

‘Shop Local’ Movements: A Solution?

Movements to bring customers back to locally owned businesses and out of big-box chain retail stores have swept America in the last 20 years. But those movements—often called “localism”—often benefit trendy and quaint white-owned businesses, including in communities of color being “gentrified” by white consumers and residents, and do not always reach minority-owned local businesses.

Olivia LaVecchia, a Research Associate with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, says communities benefit from sending as many dollars as possible into locally owned businesses—because they keep far more dollars circulating in the same community than big chains, such as Walmart, that send far more of their profits out of the state. Chains also often out-source services to other states, including where they have their home offices, instead of using local vendors.

“Our studies show that local businesses are more prosperous, resilient and more equitable. And also local businesses pay more taxes, which means the money will go back to the local government to spend the money back on the community,” LaVecchia told the Youth Media Project in a phone interview.

Still, those “localism” dollars do not always reach black-owned businesses, especially in parts of cities where white people are not as likely to go. They should, LaVecchia said.

“It’s really important to talk about localism and also how can people who want to shop around locally to make sure that they are shopping where black entrepreneurs are,” LaVecchia said. “One of the good things is that local governments have some created some good programs for this.”

Cities like Jackson participate in minority contracting practices, using businesses that are registered as women-owned, minority- or black-owned, she added. Still, it is not uncommon to hear that money from “minority contracts” are actually flowing to white men who got the contracts by having women or people of color as subcontractors, or appearing prominently on the contractor’s paperwork.

The State of Mississippi also contracts with national chains for at least some of its supplies. Across the nation, studies have shown that state and local governments often give the vast majority of their contracts to white-owned business, such as in Memphis, where businesses owned by white men got 88 percent of contract dollars between 2012 and 2014.

LaVecchia says the City of Jackson can decide to help all local businesses beyond the need for customers to support them as consumers. “There is a lot of cities can do,” she said. Cities can level the playing field, she said, by directing public money and subsidies to local businesses instead of big chains. They can also use zoning and planning policies to make sure locally owned businesses do not get squeezed out by big-box retailers. A number of cities have decided that chain businesses have to get a special permit to locate in their city limits.

But the capital issue is key, LaVecchia said. “For local entrepreneurs, particularly black owners and owners of color, the biggest barrier to start owning a business is the lack of access to capital,” LaVecchia said. ” A number of cities have loan programs for local businesses. Cities like Jackson should build “an ecosystem where entrepreneurs can own their business and grow their business.”

Learning Good Business

Part of the challenge for first-generation entrepreneurs who do not come from a tradition of successful business-owning is learning how to run a good business. In an interview with the Youth Media Project in his office, Mississippi Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann suggested that new business owners go to his office’s Y’all Business site for guidance on where and how to start a business.

“It’s got all kinds of statistical information,” Hosemann told the YMP team about the website. “It’ll tell you how many cars drive down the road in front of you. It’ll tell how good the education system is, how many hospitals are there. It’ll tell you whether or not you have wastewater-treatment plants or not. So all this great data is in there, and it’s all free. No other state has anything like this.” He said the website offers U.S Census and consumer data.

Hosemann’s sense of humor came out during the interview with his Bob Marley ringtone interrupting the interview. He quickly put his phone on silent and resumed answering a question about the pitfalls to the success of locally owned businesses in Mississippi. “Not going to Y’all Business,” he jokingly answered.

Hosemann then turned serious again. “You make good financial decisions whether to start a business or not start a business by looking at your competitors,” he said. “I can tell you how many other industries are around and where they’re located. And you look at them on a map and where they’re all structured. I think that’s the most important—your financial knowledge going into the decision process.”

Hosemann also suggested going to the Central Mississippi Planning & Development District on Lakeland Drive for statistical information.

It is vital to have a good business plan, he said, which will help a new entrepreneur figure out marketing, goals and the amount of funding they need, and then help to raise the money.

The secretary of state also suggested being creative about raising funds once you have a good business plan. “Crowd funding is when you raise money over the Internet, sometimes as much as a million dollars if you wanted to,” Hosemann added as a suggestion. “And that money is raised simply by filling out a form with your business plan on there and answering questions such as if you done this before, and what not. It is a great process for organizing your financial thoughts.”

In a recent interview with The Clarion-Ledger, Secretary Hosemann said Mississippi’s LLC start-up companies for the first quarter this year were at 6,068, compared to the same period last year that saw 5,646 new businesses.

Reclaiming Farish Street

John Tierre certainly understands the importance of a good business plan. Tierre is the owner of Johnny T’s, an upscale bar and bistro on Farish Street in the site of a historic black nightclub. He previously owned a popular T-shirt design business called Official Block Wear.

Tierre didn’t come from money. So when his grandfather loaned him $5,000 to start a business, the pressure was on for choosing his next move. “I didn’t have a lot of money to make mistakes with and lose. I didn’t come from that. So with the money I had, I had to make important decisions. Next step should be your best step,” Tierre told the Youth Media Project at his restaurant in late July.

The entrepreneur, originally from Omaha, Neb., moved to Houston, Texas, at a young age before coming to Mississippi to attend Jackson State University on a tennis scholarship in 1995. He then attended Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge, La., for graduate school.

Unlike many college graduates, Tierre became his own boss after starting a business after college. Official Block Wear gained so much popularity that he even had production in China. He also opened a promotion company, allowing him to promote concerts, clubs and venues. Then he went from from the promotion company to a barber and beauty shop, then teamed up with chef Brian Myrick to open Norma Ruth’s restaurant. Then came Johnny T’s. He has been a man of persistence.

Johnny T’s is not just a random building on Farish Street. Long before it became Johnny T’s it was the storied Crystal’s Palace, a popular nightclub in the 1930s through the early 1960s. Black entertainers such as Sammy Davis Jr., Ray Charles, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, Red Foxx, Fats Waller and others all came to there to show their talent. During a time when black people were not allowed in many places to perform, unwind and enjoy themselves, Crystal’s Palace opened its doors to them. It was one of the few places in Jackson where they felt welcome.

Keeping that feeling alive is what Johnny T’s is about. “Every chance I get, I like to tell about Red Foxx, Sammy Davis Jr., Fats Waller. We’re trying to bring that back and elevate the entertainment scene in Jackson,” he explained.

As a black business owner, Tierre supports fellow black-owned business. He orders food from the Foot Print Farms, a nonprofit farm started by black farmer Cindy Ayers-Elliott. “It’s a black farm in Jackson. No matter what it costs, we’re going to do business with them,” Tierre says.

Tierre added that his business tries to offer jobs to black people in need of one. If someone is denied a job because of there background or race, he or she is welcome to apply at Johnny T’s to be evaluated without prejudice.

The restaurateur also stresses the importance of supporting the black community in general. “If we don’t support each other, then who will?” he said.