By Kaitlyn Fowler and Maisie Brown

Additional reporting by Joshua Wright, Z’eani Furdge and Chauncey Nettles

The spray-painting of the demonstrators just added to the carnival atmosphere and elevated both the hysteria and the horror.

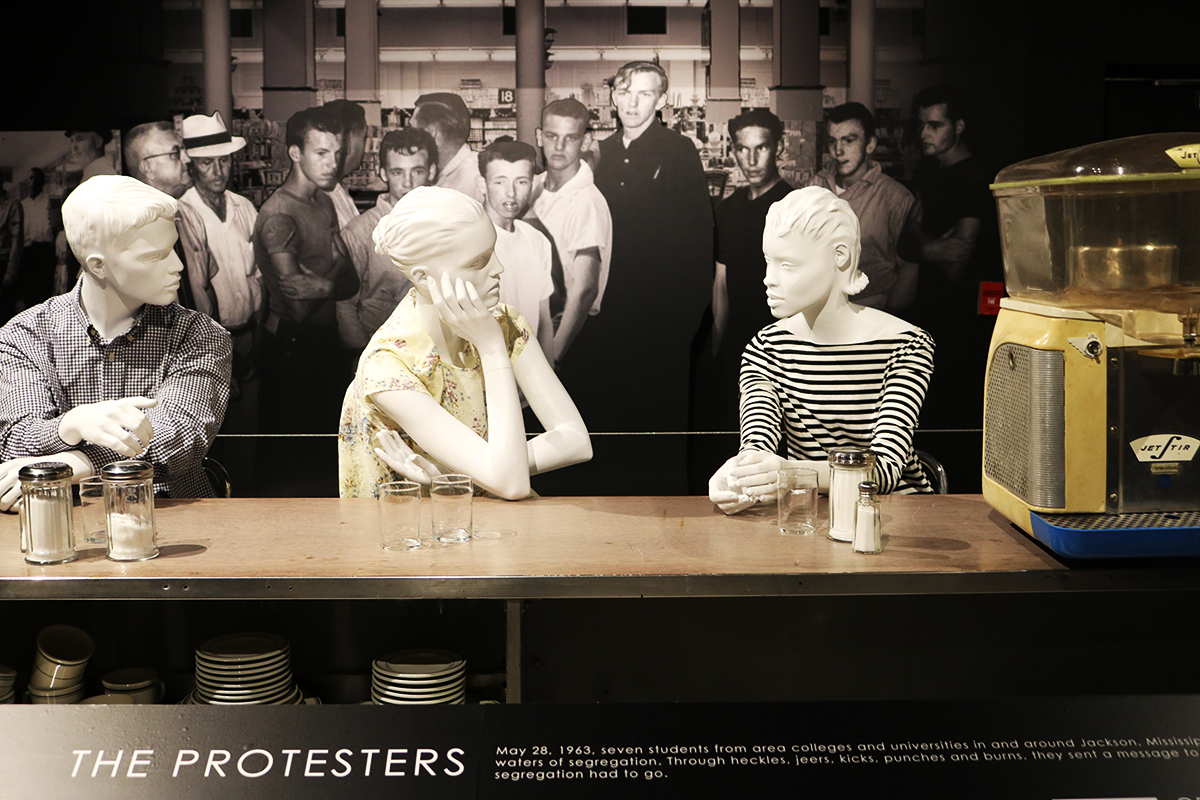

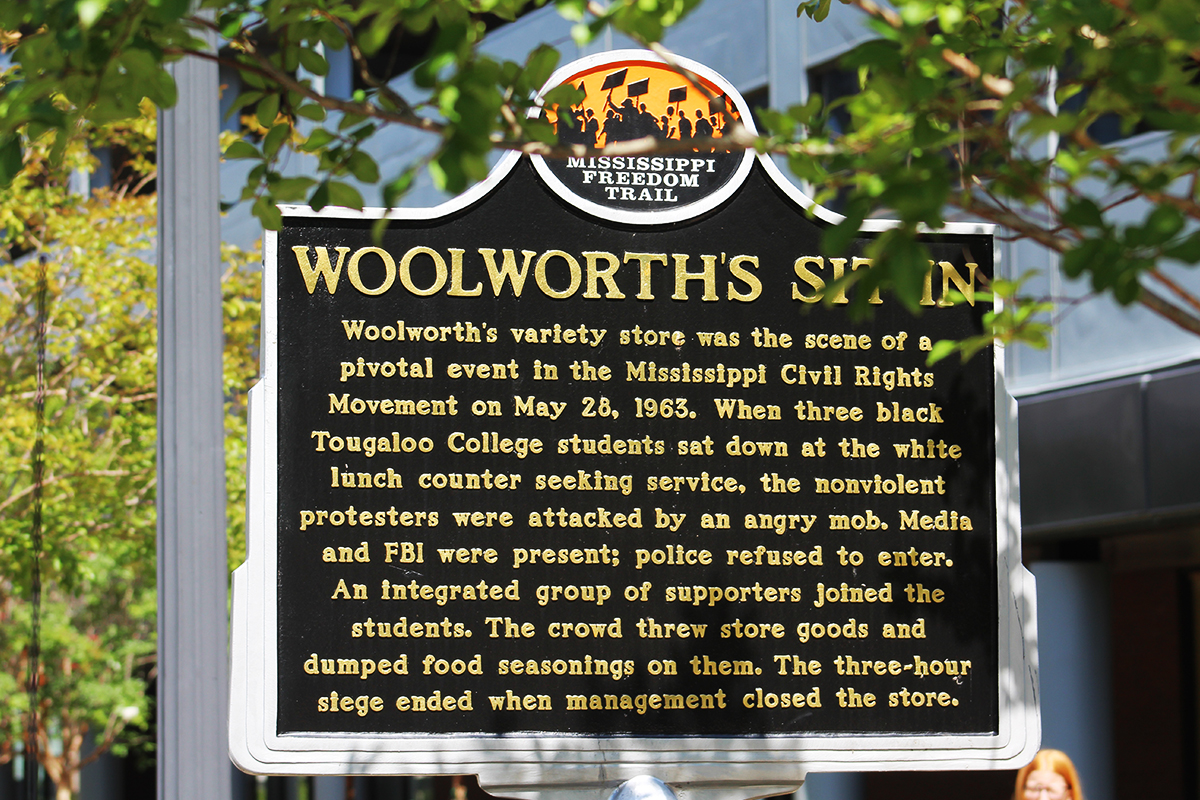

In a sea of white customers, three dark spots speckled the startled crowd at Woolworth’s in downtown Jackson on May 28, 1963. They slowly walked around the big, busy store. Posters of all sizes and color combinations exclaiming “Hot Donuts” and “Deli served fresh daily” lined the dingy white walls of the diner inside Woolworth’s in downtown Jackson, Miss.

The three dark spots, then Tougaloo College students, made small purchases throughout the store so they could not be accused of trespassing. Slowly, the students made their way to the long, worn stainless-steel counter and sat down, staring straight ahead stoically.

The two white waitresses glared in uncertainty. They were further baffled when these three spots—Anne Moody, Memphis Norman and Pearlena Lewis, the only black customers in the store—continued to calmly write what they wanted on the order slips, as if they had the right to be served just as white customers were.

“What do you want?” the white waitress asked, her eyes darting around nervously. The students started to read their food orders to her, only to be cut off. “You will be served at the back counter,” the waitress responded.

Anne Moody, a senior at Tougaloo College, was dressed in her plain skirt and shirt with short coarse, curly black hair. She maintained her composure and politely stated, “We would like to be served here.” That is, they wanted the same service as the white customers, which was illegal then under Mississippi’s Jim Crow segregation laws.

The two white waitresses glared back in the direction of the three black students and purposely turned off the lights above the counter and then dashed to the back of the store, despite white customers still being present. A couple of the other customers left the store just as swiftly as the waitresses fled to the back. The one white customer directly beside Moody slowly finished her banana split before walking away. A middle-aged white woman at the counter had not yet been served but reluctantly stood up as well, explaining she would have stayed if not for her husband. As more notice of the trio became a larger issue with white customers in the restaurant, “all hell broke loose,” Anne Moody later wrote in her 1968 book, “Coming of Age in Mississippi.”

This wasn’t the first sit-in to occur, not even in Jackson. This, however, was the sit-in that resulted in the most violent attacks and, therefore, the most media coverage.

An Angry Mob of Locals

Word of the Woolworth’s sit-in spread fast, and kids from Central High School—a nearby all-white public school that is now the Mississippi Department of Education building—trickled in. They, and the other bystanders in the crowd, noticed the clear lack of police. The crowd grew wilder, more hostile and more vocal. A few teenage boys used the end of the rope blocking off the counter and tied a hangman’s noose, attempting several times to place it around the necks of the Tougaloo students.

Norman, Moody and Lewis bowed their heads and prayed.

Unbeknownst to the three students and the majority of the crowd, Jackson Police Capt. J. L. Ray instructed Det. Jim Black to enter the store in civilian clothes. Black spotted former Jackson police officer Bennie Oliver and Red Hydrick, a local known for roughing up local NAACP leader Medgar Evers and company outside the courthouse during the Tougaloo Nine Trial.

Oliver recognized Black and approached him, saying, “If I knock that son of a b*tch off that stool, what’ll happen?”

In return, Black threatened to throw him in jail, but that didn’t stop the former cop. Oliver walked over to Norman, tapped him on the shoulder and punched him, knocking him backward onto the floor as he lost consciousness. Oliver and another man then began violently kicking Norman. Det. Black claims he started heading toward the attack as soon as it began, but others aren’t so sure.

Either way, Oliver had already stopped when Black reached the pair and arrested both him and Norman, leading them out of the store.

The crowd threw the two women students, Moody and Lewis, off their stools, and they immediately climbed back on to demonstrate the resolve of civil-rights workers to respond to bigoted attacks with non-violence. A few white Tougaloo teachers in the crowd tried to persuade the girls to leave as the mob grew rowdier. They stayed seated.

As white Tougaloo student Joan Trumpauer approached the lunch counter to join the two, a young white woman picked up a bottle of bright yellow mustard, grabbed the dress collar of Lewis’ dress and squirted the mustard down her back, shouting “Take my picture!” to the photographers. Trumpauer took a seat, but members of the white mob quickly dragged her away, with Moody pulled away seconds after. As Trumpauer and Moody fought their way back to their seats, white Tougaloo faculty member Lois Chafee joined Lewis at the counter.

By then, two black women and two white women sat at the counter. Angry white Mississippians kept throwing condiments and salt and pepper on them.

Jackson State University student Walter Williams, Congress of Racial Equality field worker George Raymond and part-white Tougaloo professor John Salter pushed through the crowd to join them at the lunch counter. Salter was immediately hit in the jaw with brass knuckles. Tougaloo’s resident chaplain Rev. Edwin King reported to Medgar Evers from a payphone as each development happened.

It was this moment when photographer Freddie Blackwell took his iconic picture of the sit-in. It shows Salter, Trumpauer and Moody at the counter. Central High student Roger Scott was a few seats down, watching the chaos. Just behind him, two FBI agents observed carefully, but did not step in.

D. C. Sullivan, the Central High student smoking just behind Moody, was contemplating the situation. He was not so much angry at the black demonstrators as he was with the white ones, he would say later. The white demonstrators were the ones devaluing themselves, he believed as the demonstrators sat, resisted and tried to have hope for change.

“Someone in the crowd then discovered Woolworth’s spray-paint aisle and began distributing cans to those closest to the counter. Suddenly, the demonstrators became human billboards, carrying the crowd’s messages in shades of pink, blue, and green. Salter had the word ‘n*gger’ sprayed on his tan jacket. On Lewis, someone wrote, ‘Won’t work.’“’Hell,’ ‘Sh*t,’ and ‘Red’ were other crowd favorites for what Trumpauer ruefully referred to as ‘body graffiti.’ The spray-painting of the demonstrators just added to the carnival atmosphere and elevated both the hysteria and the horror.”Moody and Salter attempted to talk about a final exam as the melee continued until it became too difficult. A. D. Beittel, the Tougaloo president, sat down to join them. The loud speaker announced that the store was closed three hours after the sit-n began, and the crowd began to thin. Rev. King and Mercedes Wright, spotters for the demonstrators, made their way to the counter to help the students to the cars, getting police protection only for their trek from the door of the store to the vehicles.

By the end of the night, the sit-in at Woolworth’s had received national attention. The next day, students from Lanier High School and Brinkley High School, both segregated with black students only, sang freedom songs and marched during their lunch hour. The following day, close to 500 students from five high schools marched, and almost all of them were arrested. When the police ran out of room in the police cars, the students were transported in garbage trucks to the state fairgrounds, where they were put in livestock pins. Over the next few weeks, white supremacist Byron de la Beckwith assassinated Medgar Evers in front of his wife and children; John Salter was injured and hospitalized; and Ed King went to jail. The mayor agreed to only three of the eight goals of the NAAEP’s goals for racial equality, but the committee comprised of the Jackson Movement’s representatives and the mayor’s designees had little choice but to accept the terms, as their major players were out of the game.

It would be five years after the violent sit-in before segregation of public spaces became illegal under federal law. Even then, the fight wasn’t over.

Once Seen, It Cannot Be Unseen

Robert Luckett, a white history professor at Jackson State University who specializes in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, says the struggle for black freedom and equality is still continuing 54 years later.

“It isn’t like you could say, ‘[In] 1968, Dr. King died, the movement was over.’ People have continued fighting ever since for civil and human rights. The truth is we’ve always had a Civil Rights Movement in this country,” Luckett said in an interview at the Youth Media Project.

“If you go back to the day the first enslaved African arrived on the shores of Jamestown, someone was fighting for his or her right to be free. They didn’t want to be enslaved. The movement is something that is ongoing.”

A modern example is the Black Lives Matter movement. #BlackLivesMatter started trending in 2012 after a self-proclaimed security guard George Zimmerman killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin because he said he felt threatened by the unarmed teen. A jury later exonerated Zimmerman.

The BLM movement quickly became a way to resist the long-common policing killings of often-unarmed men of color as cellphone cameras brought the practice to a larger public stage. This had a similar effect to the 1960s when protesters such as those at the Woolworth’s lunch counter invited media to witness how black people were routinely mistreated in the Jim Crow South.

In the face of discrimination and lack of safety, Black Lives Matter takes a stand for “black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, black undocumented folks, folks with records, women and all black lives along the the gender spectrum. It centers those that have been marginalized within black liberation movements,” as the BLM website states. It aims to call attention to the deprivation of basic human rights and dignity that black people, and other people of color, face daily.

Motivation for the Black Lives Matter movement is similar to the Civil Rights Movement, Luckett says.

“Today, we think about Black Lives Matter, and as a movement, many of the things it has operated around and been motivated by are images,” he explains. “We can see this happening, and it’s the same thing during the Civil Rights Movement. The movement got motivated because of the images of this mob attacking (at the sit-in), because of police dogs and fire hoses in downtown Birmingham, because of the body of Emmett Till. Images have always driven activism.”

This could not be more apparent than in the picture of Leshia Evans, a nurse and a mother from Pennsylvania, taken at a protest in Baton Rouge, La., in 2016 after police killed Alton Sterling. She stands alone, but strong, in a flowing dress, face to face with a row of heavily armed police officers.

“There are images that are impossible to forget, searing themselves into our collective consciousness,” Yoni Appelbaum writes in The Atlantic. “One man staring down a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square. A high school student attacked by police dogs in Birmingham, Alabama.”

Three people peacefully sitting at a lunch counter, being doused in food, drinks and condiments, covered in trickles of blood and spray-painted with vulgar insults. Bennie Oliver brutally kicking a defenseless Memphis Norman while others, including law enforcement, look on. White faces smiling and jeering as the hysteria continues.

“This is such a photo,” Appelbaum continues about the picture of Evans in Baton Rouge. “Once seen, it cannot be unseen.”

Shortly after the photo of Evans went viral, she released a statement. “When the police pushed everyone off the street, I felt like they were pushing us to the side to silence our voices and diminish our presence,” the then-35-year-old woman said. “They were once again leveraging their strength to leave us powerless. As Africans in America, we’re tired of protesting that our lives matter. It’s time we stop begging for justice and take a stance for our people. It’s time for us to be fearless and take our power back.”

Evans was one of about 100 protesters arrested a few days later, but the fire was already lit for the BLM movement. Almost anyone, when given a basic description of this image, knows the exact picture. Both this picture and the images from the sit-in at Woolworth’s highlight a clear contrast—the calm of the demonstrators against the danger and unpredictability of the storm.

In fact, it wasn’t until he took pictures at the Woolworth’s sit-in that Freddie Blackwell opened his eyes to brutality by people of his own race, “It hit me when I was photographing that they were right and we were wrong,” he said, explaining his abrupt realization.

‘Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired’

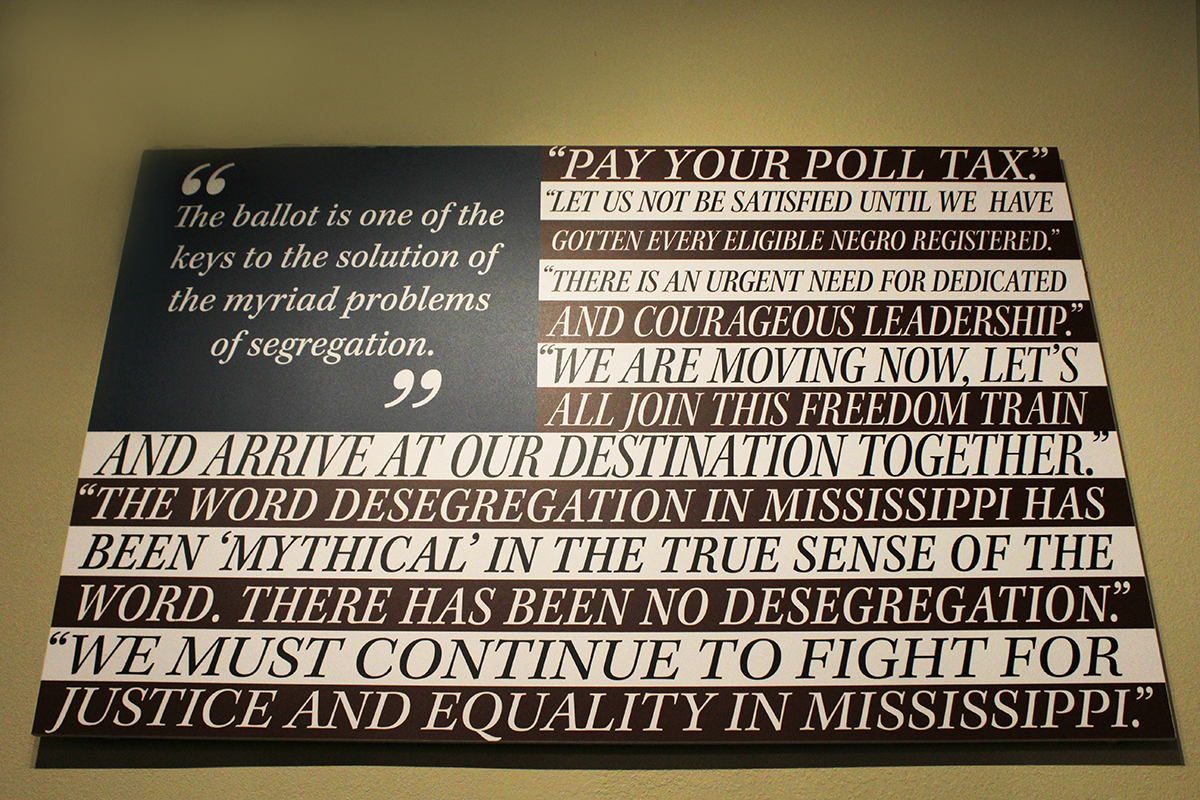

Photos are not the only thing that have power in a movement. So do words.

Delta sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer’s memorable quote about treatment of black Mississippians, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired,” still holds weight 50 years later.

Michael Brown cried out, “I don’t have a gun. Stop shooting,” before he died with six bullets in his body.

Sixteen-year-old Kimani Gray begged to a woman close by, “Please don’t let me die.” It was too late.

Philando Castile‘s girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter, Dae’Anna Reynolds, was caught on video, just after witnessing Castile’s death, telling her mother, “I don’t want you to get shooted.”

Eric Garner begged to New York police officers to stop choking him. “I can’t breathe,” he said 11 times. He died.

His crime? Selling loose cigarettes. The phrase, like many others, turned into a rallying cry; Yale librarians named it 2014’s most memorable quote. In December 2014, Washington Post writer Elahe Izadi wrote, “Will Garner’s final words—and the debate about race and the criminal justice system to which they’re now connected—fade from public consciousness in a year or two?”

The apathy problem is captured in a psychological concept termed the “bystander effect”, or “bystander apathy.” It is a social psychological phenomenon in which individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present.

Joshua Quinn, founder of Brothers Against Racial Stereotypes (BARS) Institute, speaks of the bystander effect. “You’re not affected by it because you’re not there, but just knowing that it could happen to you, seeing all the black bodies lying around with police brutality and things like that, that’s traumatizing,” he said in an interview at the Youth Media Project.

Quinn says depictions of brutality against black people such as at the Woolworth’s sit-in, or videos of Garner repeating “I can’t breathe,” are deeply painful for African Americans. “Words and images like that, it gives you this conflicting thing. W.E.B Dubois calls it double consciousness where you’re trying to figure out whether you’re African, whether you’re American and trying to keep yourself together, being both,” he said.

Paying Lip Service

Pastor Keith Quinn always sat down and told his son, Joshua, about important but generally unknown events in the Civil Rights Movement. “You’re not going to get this type of information, or you’ll get the diluted version of the information in school, so I’m going to give you what actually happened,” he would tell young Quinn.

The adult Quinn says that many of the things that his father mentioned to him had been neglected in his classrooms. Teachers tend to stick to the curriculum, and the curriculum glosses over or removes the parts of the story that tend to be more personable to young people, such as their hometown, or sitting at a “whites only” lunch counter, or the inhumanity and indignity of being spraypainted with ugly words or coated with mustard.

Quinn was in Chicago after the death of Trayvon Martin and watched the dynamics of the Southside as it erupted in protests and demonstrations. He agreed that something had to change, but all he saw in the protests was lip service, not action, he says. Quinn compares the cycle of police brutality and oppression to a domestic-violence scenario.

“You’re always taught to forgive, but we have nothing to protect that forgiveness,” Quinn says. “If they know you are going to keep coming back, the abuse is going to continue.”

The protesters were speaking up about the problem but not doing anything about a major source of the problem—young, black girls and boys who aren’t learning everything they should be learning, particularly about the history and specific details of the Civil Rights Movement, Quinn says. He returned to his hometown, where he founded the Brothers Against Racial Stereotypes (BARS) Institute, a program that helps educate young, black boys. Quinn makes sure they learn about things that they can go out and experience, such as teaching them about wealth, class and race using Jay-Z’s recent song “The Story of O.J.”

The chorus in “The Story of O.J.” essentially says that no matter what shade of black you are or what financial status you represent, if you are black you are still a part of the black racial group and therefore treated differently than you might be if you were not.

“That’s not something common in regular school, but that’s what they identify with,” Quinn says of the boys.

BARS Institute helps educate and nurture black youth in ways that they understand and in areas that the school system sometimes neglects. Quinn strives to push back racial biases by getting to one of the roots of the problem: the inaccurate and demeaning narrative about young black men. One way to do that is through teaching about their real history.

Pamela Confer, who has been on the board for the Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center where the Woolworth’s Sit-in exhibit opened in summer 2017, says that the fight for fair treatment of African Americans and other people of color has to be fought on many different sides.

“Each of the different pieces of wood on a fence makes the whole fence,” Confer says, “You’re not going to stand one piece of wood, but that one wood that you’re going to have for each part of that fence is going to be equally strong, or the whole fence begins to sway anyway. I am a piece of wood on a fence, and I am strong and I am invincible whether people stand with me or not. That’s the way that we all should think, because eventually another piece of wood is going to go there, just as strong, and then another piece of wood, and then we are a fence.”

Joshua Quinn and BARS Institute is a piece of wood on that fence, as is each of the boys participating with BARS. Programs connecting youth and police are a piece of wood on that fence. The new Woolworth’s Sit-In exhibit is a piece of wood on that fence. The Woolworth’s Sit-In on May 28, 1963, was a piece of wood on that fence. Every single person who believes in something has the capability of being a piece of wood on that fence.

“What counter, figuratively, are you going to sit at?” Confer asks. “What role are you going to play and let the world dump on you mustard and ketchup and condiments? You’re going to let the world dump on you so that you can try to make the world a better place. What is your mustard? What is your ketchup? What is your salt? What is your water? What is your drink that you’re allowing the world to dump on you so that can help make the world a better place?”

To hear more about the BARS Institute, listen to YMP students interview Joshua Quinn in the podcast below.

[soundcloud id=’335998430′ height=’false’]

This Woolworth’s Sit-in package is a group project in the summer 2017 Mississippi Youth Media Project class.