By Aja Purvis, Leslyn Smith and Ruben Banks

Additional reporting by Shakira Porter and Raha Maxwell

John Knight, 15, and a friend were walking near his grandmother’s house in the Washington Addition under a beaming sun on July 7, 1991. Knight was dressed in shorts and a T-shirt when they walked up to the creek he had learned how to swim in. They started to explore.

Suddenly, Knight saw a .22 revolver lying near the creek and bullets nearby. Holding the gun in his hand, Knight began aiming at small crawdads and turtles in the creek.

“Pow! Pow! Pow!” The sounds of gunshots round out.

“Oh, my turn! my turn!” Knight’s friend yelled.

With approximately 200 bullets, Knight and his friend took turns shooting the gun at small crawfish and turtles in the creek. Then, as he handed the gun to his friend, Knight saw a policeman coming into view behind his friend.

Knight quickly put his hands in the air for the officer. “Don’t shoot it, don’t shoot it! It’s the police!” he started yelling out to his friend, who soon began raising his arms as well. Before them stood an old white police officer, shaking with his gun in his hand.

This was the first of three times that John Knight, now 40, was arrested.

Picture this: Frontage Road, Highway 80, outside of a Chinese Restaurant, also in 1991. Knight had started home from the restaurant with his friend. They were walking in a familiar alley when an unmarked police car came into view.

Suddenly, a narcotics police officer accompanied by another officer began calling out to the two boys from the window of the car. Quickly, the two officers got out of the car.

“What are y’all up to?” a black officer inquired, grabbing the styrofoam containers holding Knight and his friend’s food, then throwing them on the ground.

“Get on the car!” The other officer yelled. In seconds, the officers were pushing Knight and his friend onto the cop car to pat them down.

“He’s clean,” an officer said, after checking Knight’s friend, so he let him go on. Knight was also clean the first time the officer patted him down. As he began to walk away, an officer called out, “Hey, that’s that little Knight boy that be at the 24-hour store!”

Grabbing Knight and searching him a second time, the officer felt a little matchbox in his sock, which led him to search his socks. Opening it, the officer found Knight’s marijuana stash.

“I had some drugs in my sock that I thought they wouldn’t find. We were really just trying to catch us a lick, and we ended up being the lick,” Knight said in an interview at the Youth Media Project.

It was his second time getting arrested.

“That started a trend that I just couldn’t seem to get away from because I wanted to have more so bad, and I wanted to get out of the situation I was in that I continued to allow myself to get deeper and deeper in the pit out there in them streets,” Knight said.

Over time, Knight went to prison three times and served a total of 26 years. Now, he wants to keep other young people from making similar mistakes.

Meet ‘the Parent of Crime’

“‘Poverty,'” Aristotle wrote, “‘is the parent of crime.'”

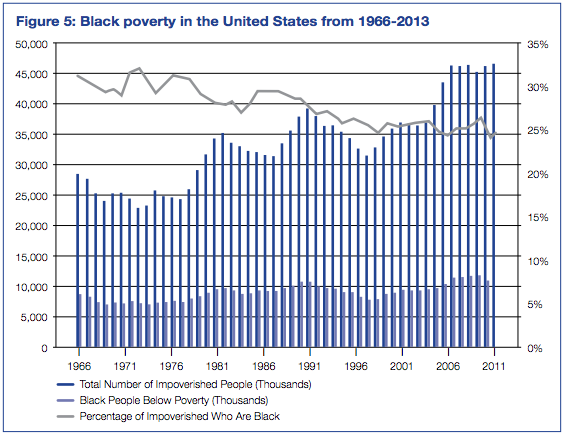

Crime researchers do not shy away from one of the primary reasons that many young people end up in jail or prison. “Poverty and crime combined together leave people with two choices: either take part in criminal activities or try to find legal but quite limited sources of income—when there are any available at all,” Dario Berrebi, a filmmaker and researcher who works to raise awareness about poverty, said on his website.

Like John Knight, many young people are growing up in Jackson in poor neighborhoods with limited opportunities in cycles of poverty passed down through the generations. ”I ventured out at an early age to do things to try to help my mother, better our lives to keep us from being poor because she worked two jobs, and we still struggled,” Knight told the Youth Media Project.

The Youth Media Project offices in Capital Towers has a wall of many causes of youth crime that Wingfield High School student journalists started in spring 2017. Several of the causes they identified are related to young people growing up in poor conditions: few job opportunities, limited transportation, homelessness, insufficient school resources and teachers, and the cost of living dwarfing their insufficient income.

Interviewers for the 2016 BOTEC Analysis report on Jackson crime, funded by the Mississippi Legislature, talked to adults and young people throughout Jackson and found that unmet basic needs often lead to crime and violence here.

“Responses from youth of Jackson often focused on issues of poverty, from hunger to neighborhood blight,” the BOTEC report, “Precursors of Crime in Jackson: Early Indicators of Criminality,” stated. “When one young participant was asked what she would do to solve the problem of crime for people living in Jackson if she had unlimited resources, she replied simply, ‘Feed them.‘”

BOTEC said that of 30,000 students enrolled in Jackson Public Schools, local police or the Hinds County Sheriff’s Department will arrest about 5 percent, or 1,500 students, and 2.2 percent for a serious crime. It found two primary precursors to young people entering increasingly more serious crime cycles. One is a high rate of school absence or dropping out; the other is being arrested as a minor, as Knight was when he shot at crawfish in his childhood watering hole.

“An individual arrested as an adult in Hinds County or Jackson is 240 percent more likely to have dropped out of school at some point, 160 percent more likely to have been involved in the juvenile justice system, and 67 percent more likely to have been chronically absent while enrolled in school in Hinds County,” BOTEC found. Those arrested for serious or very serious crime were even more likely to have dropped out or been chronically absent.

Knight, for instance, dropped out of school in his early teens, and he was arrested twice when he was only 15.

The Mississippi Division of Youth Services’ 2016 Annual Report reported that the top 10 offense categories for Hinds County juvenile are burglary, drug offenses, domestic violence, weapon offenses, simple assault, disorderly conduct, running away, malicious mischief, and petit larceny, and grand larceny.

BOTEC connected the dots about young people who get in trouble in Jackson to the results of poverty and its symptoms: “The majority of our participants who later ran into trouble with the criminal justice system described upbringings that were full of losses, danger, and instability. Elements of dysfunction included poverty, disabilities, boredom, and lack of adult attention, death or absence of parents, often resulting from addiction or incarceration.”

The study recommends focusing prevention efforts heavily on the percentage who have experienced the top two indicators of criminal behavior—dropping out and being involved in the criminal-justice system—for a primary focus population of 225 students.

BOTEC warns, though, that it will take more than juvenile arrest and detention—which increases the chance of prison later—to help this target group. “The population represented in these accounts is for the most part poor, with childhoods marked by loss, violence and neglect,” the report warned.

The crime-analysis wall at the Youth Media Project proves this point. Many of the causes of crime lead straight back to generational poverty.

‘That’s by Design. That’s Race.’

Johnnie McDaniels agrees with the YMP student analysis that youth-crime causes are wide and varied, but still often connected to poverty and other cyclical and under-treated conditions. The executive director of the Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center sees a lot of young Jacksonians ensnared by crime come into the detention facility.

“I worked as a prosecutor in the city of Jackson for 10 years, and one of the things that you became very aware of early was that there was a direct relationship between juvenile delinquency and adult crime,” McDaniels said, echoing the BOTEC findings.

McDaniels was raised in a rural community in Claiborne County, where he spent a lot of time with his siblings and watched “educational programs and legal shows.” This led to him wanting to become a lawyer.

But not every young person has that path open to them. “Young people get involved with crime for a multitude of reasons, some because of learning disabilities they’ve had since they first entered school, related to teasing, bullying and other things that cause them not being able to function in school,” McDaniels said. “Others because of dysfunctional families, circumstances they’re living in; others because of the communities and environments that are around them.”

Henley-Young is a facility that provides temporary care for minors requiring secure custody pending court study and disposition. The facility is under a federal consent decree for traditionally poor conditions and care for the young people housed there—conditions that are starting to change.

The U.S. Department of Education confirms that many children face deep problems that ultimately can lead to crime: “[N]early 30 percent of students are either bullies or victims of bullying and 160,000 kids stay home from school. More than 30 million children are growing up in poverty. In one low-income community, there was only one book for every 300 children.”

McDaniels does not mince words when it comes to the reason for this cyclical, entrenched poverty in so many neighborhoods of color. “This is about institutional racism, this is about the structural racism in America that prevents black people from being able to find employment. We have poor schools. We have poor everything.That’s all because of structural racism,” he told the Youth Media Project.

“Structural racism” is much deeper than interpersonal bigotry. The Aspen Institute defines it this way: “A system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity. It identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with ‘whiteness’ and disadvantages associated with ‘color’ to endure and adapt over time.”

Experts say this baked-in racism has caused decades of generational poverty and crime, made worse by inadequate educational opportunities, inequitable funding of schools, and few after-school options for young people growing up in poverty. That means they too often turn to crime, especially during the worst time of day for youth crime—right after school.

McDaniels points to Jackson’s history of white and economic flight that exploded after public schools here were forced to integrate in early 1970, leading thousands of white families and their property taxes to flee to private schools and, over time, to the suburbs. “We have poor schools for a reason. That’s by design. That’s not by accident. That’s because of race,” the juvenile-detention director said. “We have poor neighborhoods and communities by design and because people decide where people live based on their income. That’s by design. That’s race.”

Cycles, Bundles and Layers

At approximately 4 in the afternoon, it began: the yelling and uproar motivated by bundles and layers of anger in a house under the summer sun.

“If you leave out of this house, I’m calling the police!” Lakeisha May’s* mother yelled at her. Wearing her black shirt and blue jeans paired with black Nikes and a blue polo hat, May stormed out of her home.

As May, then 14, walked to a track meet at Northwest Rankin, all she could think about were her mother’s words: “You can’t play basketball anymore!” May also had a feeling her mother would follow through with what she had said and call the police.

When she arrived at the opening gates of the football field, May stopped at a small, gray LIFETIME-branded table, and handed $20 to the woman behind it. She had to pay since she was no longer on the team.

After admission, May walked up to her former track teammates and a friend and began to tell her story. “I walked out of the house, and my mom said that she was going to call the police, so keep a look out,” she told them.

“You bad,” her friend said.

“No, I’m not,” May responded.

May stood around with friends, enjoying the Mississippi weather until her friend exclaimed, “There they go!”

An officer came into view near the gates where May had entered and yelled, “Come here!” when he spotted her.

Thinking fast, May ran into a nearby restroom close to the football field. “They can’t come in here,” the teenager told her friend.

“You better run to the other side! You better hop the fence,” her friend suggested from outside the restroom.

May took off, but her shoes weren’t tied, so she could not move very fast. Suddenly, her hands were being placed behind her back, and she was being handcuffed.

“I wish you wouldn’t have ran,” a sympathetic voice commented, as the Flowood police officer escorted her to the backseat of his cop car.

“It’s just a negative vibe at home. Basketball was like a getaway,” May explained to the officer as he drove her to the Rankin County Juvenile Detention Center in Pelahatchie, Miss. That day was May’s first day going to a juvenile-detention center and her first of four times being put in the back of a police car.

“Me and my mom are always into it before we’re right back talking to each other,” May, who has attended the Youth Media Project, said while recalling the event. “We need to get on the right track and be able to talk to each other a little bit more than we do.”

The BOTEC reports on Jackson crime predict the cycle that May has followed so far—more detention and prison often follow detention. “Those involved in the juvenile justice system are more likely to be criminally active as adults,” it warned.

”Statistics and data and research show that the first contact that a young person has with law enforcement decreases the likelihood of their positive outcomes in life and increases the likelihood of them going through the criminal system later in life,” Rukia Lumumba, an attorney, transformative justice strategist, activist and daughter of the late Mayor Chokwe Lumumba, told the Youth Media Project.

The National Institute of Justice study, “From Juvenile Delinquency to Young Adult Offending,” warned about this recidivism cycle. “Continuity of offending from the juvenile into the adult years is higher for people who start offending at an early age, chronic delinquents, and violent offenders. The Pittsburgh Youth Study found that 52 to 57 percent of juvenile delinquents continue to offend up to age 25, ” it reported.

The Mississippi Division of Youth Services’ 2016 Annual Report found that the frequency of youth entering the criminal-justice system is highest between the ages of 13 and 17.

McDaniels points to conditions at home that often put children into negative cycles. “Most of the youthful offenders, the 10- and 11-year-olds (often are involved in) some type of domestic violence where they’re fighting with brothers and sisters, or they’re fighting with mom or that type of thing,” he said.

Likewise, Wingfield students identified domestic violence as well as a cause of violence in their crime analysis that now covers a large wall in the YMP learning space.

One problem leads to another and can get progressively worse if not interrupted, McDaniels warned. “The 13- to 14-, 15-year-olds tend to begin experimenting with drug use, so that’s where you’ll find your possession of marijuana, shoplifting and crime of that nature because of trying to address a particular habit they may have,” he said. “Older teenagers tend to get involved in more violent offenses, and that’s when you begin to see the kinds of crimes that they could end up being charged as adults for. A lot of them end up in the adult system because they commit adult crimes: murder, rape, robbery.”

As BOTEC warned, that violent criminal often starts with a young person entering the system for a minor offense, which often begins with young children making mistakes, especially in poorer neighborhoods where young people have few options and parents are either absent or working several jobs to make ends meet.

This tracking into a life of crime even has a name—the “school-to-prison” pipeline, also known as the “cradle-to-prison” pipeline.

School-to-Prison Pipeline

Poor-quality and under-funded education plays a big role in youth crime. For many reasons, school does not always catch the interest of every student. “Participants across the study reported chronic boredom and lack of engagement in school, and many made a direct connection between boredom and getting caught up in antisocial and illegal activities,” the BOTEC researchers stated.

The idea of the “pipeline” is that certain young people—often children of color—get caught up in a discipline-detention cycle that spirals them into an ever-worsening life of crime if it is not stopped. Treating young people the same as adult suspects, especially for minor offenses, by handcuffing them, throwing them face-down on the top of a cop car or taking them to detention in the backseat of a police car are all ways to track them into the devastating pipeline. Some call it “cradle-to-prison” because young children can get caught up in it as well, such as a former YMP student who was first sent to juvenile detention in the fourth grade for breaking into his elementary school.

“The School to Prison Pipeline describes local, state and federal education and public safety policies that operate to push students out of school and into the criminal justice system,” an NYCLU report explains. “This system disproportionately impacts youth of color and youth with disabilities. Inequities in areas such as school discipline, policing practices, and high-stakes testing contribute to the pipeline.”

McDaniels of Henley-Young says students who fall in this pipeline usually have certain experiences in common. “They get labeled, and often times once they get labeled, they are immediately put into what you call the school-to-prison pipeline where behavior that usually would be handled by teachers and by principals is now handled by the criminal-justice system,” he said at YMP. “So they are ushered into the criminal-justice system that’s not designed to effectively treat a lot of the issues that they have.”

The Children’s Defense Fund found in its study, “Are Suspensions Helping Students?” that black students were suspended two to three times more often than white kids. But the research of Dr. Russell Skiba, psychology professor and director of the Equity Project at Indiana University, shows that young people of color are not getting suspended because they are more crime-prone. In fact, he found, they are often suspended or expelled for lesser offenses—such as looking out a window in class or “talking smart”—than the offenses that get white kids kicked out of school.

Attorney Matthew W. Burris wrote in “Mississippi and the School to Prison Pipeline” that the kinds of punitive school discipline many school districts dole out actually feed the cycle of crime—precisely because children are pushed out of school exactly when they need to be there.

“Faced with insufficient funds and a perverse incentive to push out low-performing students,” Burris wrote, “many schools have embraced zero-tolerance policies. They have resulted in an explosion of school suspensions, expulsions, and arrests that unfortunately contribute to and reinforce the School-to-Prison Pipeline. Studies show that a short exclusion from school disrupts the student’s education and increases the likelihood that the student drops out, commits a crime, and later becomes incarcerated as an adult.”

The “school-to-prison pipeline” is built off “zero tolerance” policies that gained popularity in the 1980s after the crack epidemic, causing massive suspensions and expulsions of young people of color, especially, and the influence of the “War on Drugs” ideology. Experts such as McDaniels and Burris explain that the school-to-prison pipeline acts as a systematic form of oppression, preventing the success or prosperity of youth with disabilities or poor performance in school by molding their mindsets into criminality.

”There are many reasons why that exists. Some of the reasons—the main reason—is a result of slavery and the lack of abolishing, truly abolishing it,” Rukia Lumumba said. “Our prison system is another form of slavery. There’s no question about that, and our system for children—the jail system for children started back in the 1800s when Puritans created these schools to control children, to mold them … (because) children were born into the world evil, and you needed to take the evil out of them.”

“So when you have two systems who have its roots in very toxic dehumanizing institutions, we got a problem,” she added. ”The system is biased. It is racially biased, and it’s not only racially biased, it’s class biased.”

Research data back her up. “Race and sex are arrest risk factors. Being black and male is highly correlated with having been arrested by Jackson Police Department or Hinds County Sheriff,” Jackson’s BOTEC Analysis reports.

Data from the Mississippi Division of Youth Services’ 2016 Annual Report reveals that Mississippi’s intake of juvenile delinquents consists of 1,054 white females, 2,005 white males, 1,964 black females and 4,018 black males.

Among these young people, research shows that black delinquents are more likely to be detained for less offensive crimes as compared to their white counterparts, similarly to Russell Skiba’s findings about school discipline. They are more likely to serve a longer sentence for the same if not lesser crimes as white youth. That trend reversed for a while starting in the 1980s, but returned in the last decade.

“For black juveniles, the likelihood of delinquency adjudication decreased between 1985 and 1994 (from 57 percent to 53 percent) and then increased to 56 percent in 2009,” the National Estimates of Delinquency Case Processing reports.

Studies from 2013 show that the rate per 100,000 juveniles for blacks was 73.8, while whites had a rate of 32.2, the Racial Disparities in Youth Commitments and Arrests reports. Out of every 10,000 teenagers, 738 black juveniles are arrested compared to 322 white juveniles.

Growing Up in Chaos and Trauma

A daunting bottom line for many black children is that they are growing up in chaotic situations, often experiencing deep trauma due to the violent cycles they have inherited. “It’s important that you provide young people with outlets to deal with issues that they have,” McDaniels said at YMP.

“Those who are involved with the criminal-justice system oftentimes suffer some type of trauma,” he added. “Or, they have suffered some type of mental illnesses. They have suffered some type of drug addiction. They have suffered some type of serious violent act, and you have to work with kids with those types of issues. And you can’t do it on a one-time basis.”

Knowing the problem makes it easier to address or prevent it. “The prevalence rate of youth with mental disorders within the juvenile justice system is found to be consistently higher than those within the general population of adolescents,” Lee A. Underwood and Aryssa Washington wrote in a 2016 article for the Mental Illness and Juvenile Offenders. “Estimates reveal that approximately 50 to 75 percent of the 2 million youth encountering the juvenile justice system meet criteria for a mental health disorder. Approximately 40 to 80 percent of incarcerated juveniles have at least one diagnosable mental health disorder.”

Adverse Childhood Experiences—referred to as “ACEs”—can have great negative effects on a young person’s mental health, sometimes leaving a lot of damage that continues into adulthood. An ACE study by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that the negative experiences fall under three categories: abuse, neglect and household dysfunction. The study shows how common ACEs are and the effects they have on children as they enter adulthood, shaping the kind of adults they will be. ACEs include physical, emotional and/or sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; mental illness; incarcerated relatives, mothers treated violently; substance abuse; and divorce.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation study found that 64 percent of 17,000 participants “had at least 1 ACE,” showing how common they are and how easily exposure to traumatic events can affect young people.

Jackson’s BOTEC Analysis report also made a connection between mental health and poverty: “Lack of access to mental health care is also linked to crime in Jackson. Participants in the study who lived in poverty mentioned frequently that they or family members needed mental health treatment, but failed to receive it. Many felt that they or their loved one have been misdiagnosed. Some participants mentioned being prescribed drugs, but not getting counseling.”

Poverty exists outside the jail systems as well and often drives crime because of the lack of access to necessities, such as treatment for mental illnesses. Young people can be affected both by suffering from mental illness and trauma, and by being exposed to circumstances that may lead to the development of an ACE.

“What we have tried to do is say, ‘Look, we can’t treat each case the same. We have to get into the facts and circumstances associated with it,” McDaniels said. He offered a basic solution: early involvement in young people’s lives, especially those at high risk of ACEs.

“So we’ve been able to say this kid here, you know, has been in Henley-Young since he was 13. He’s committed these types of crimes, and based on the type of crime it is, we can pretty much determine whether or not that kid is going to graduate into the adult criminal-justice system. So we have to get involved earlier on,” McDaniels said.

Henley-Young’s mission is to give juvenile delinquents safety, security and stability, while improving their well-being. “We have programming there for the entire time a kid happens to be in that facility. We have programming to address those type of issues,” McDaniels said.

The director of the Mississippi FBI agrees. Special Agent in Charge Christopher Freeze, the man who may arrest some young people with ACEs once they turn 18 and commit serious crimes, is pushing for “more attention to the conditions juvenile face,” Freeze said in a July interview at the Youth Media Project.

Freeze agrees with McDaniels that all young people need opportunities to get involved in activities that can redirect their energies away from the streets. “We cannot arrest our way out of this law-enforcement problem. … (We) must be involved in programs that provide escape,” Freeze told the Rotary Club of Jackson in April.

Avoiding ‘The Devil’s Workshop’

“An idle mind is the the devil’s workshop,” criminal-defense attorney and former Hinds County Chancery Judge June Hardwick said in an interview at the Youth Media Project. “Studies have shown that crime is most committed by juveniles between say about 3 p.m. when y’all get out of school, and say 7 p.m. or so.”

Hardwick is a former teacher who went to law school when she became a single mother to Raha Maxwell, now a Youth Media Project student, after police killed his father, Shawn Maxwell, in Seattle, Wash.

Olivia Coté is a current ninth-grade teacher at Murrah High School, who also volunteers at the Youth Media Project. She is a dynamic teacher who encourages young people to write about their own experiences—from writing poetry about their families to tackling social-justice issues in their work.

“I think education is one of the biggest parts of committing youth crime and that if we can keep students engaged in school, then they’re less likely to want to miss school,” Coté said. “Or they’ll be more motivated, you know, to do well and they will wind up maybe getting suspended less.”

John Knight emphasizes that he liked school and made good grades. But his family was living in poverty, and his single mother could not provide well for him and his siblings. “The decisions that I made, I made them thinking it was going to make life easier for my mother and my brothers and my sister and myself. And it did, but it also made it harder, and struggle became real because I was out there in the streets where people was getting killed and people having to kill to do what they had to do to get money,” he told YMP.

Knight says making good grades, and even making the honor roll, helped “keep attention off me being poor, or me wearing the same dirty shoes, the same pants three times a week. I cracked jokes, and I drawed, and I made sure people liked me. That’s why I’m a people person now—because I didn’t want to be the center of the wrong attention by being poor,” he said.

Growing up in his circumstances was traumatic, Knight said: “I made ways to keep people away from downing me, and also to keep me from sinking down into a deep depression of wanting to have different things in life and wasn’t able to get it through my mom, you know what I’m saying?”

Jackson’s new mayor is working to change the narrative about youth crime from just police enforcement and into alterning the conditions that cause it. “Crime is not only about how you police those issues, but it’s about the conditions which give rise to it. I think poverty is a significant contributing factor to crime,” Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba told the Youth Media Project in July in his City Hall office. “If we want to tackle the issue of crime for youth, we have to look at the social-work component of that and how we engage young people.”

‘Repositioning the Thoughts’

By the time John Knight got arrested the first time for firing at crawdads and turtles when he was 15, his grandmama had long been telling him, “Don’t get yo name on that book! Do not get yo name on that book, John!” She meant that he must not get a police record because she knew he would just “keep going” and start a cycle it would be hard for him to escape.

“She wasn’t lying, you know what I’m saying, because it’s just been going on ever since then, man,” he said at the Youth Media Project.

The main problem juvenile offenders face, Knight said, is that the system does not really try to help them not re-offend. He uses the example of breaking your leg and then getting therapy for it to work right again. That does not happen for most young offenders, especially if they’re African American.

Knight, though, does not just blame the system for the cycle of crime too many young black people get caught up in. “It’s us. We keep the cycle going, too. When they don’t give you an outlet to go a different route, you don’t have no choice but to go back to the seeds from which you planted from the door.”

The former drug dealer is not confident that the cycle can be stopped, but he believes community members can “curb it a little bit by really caring.”

What happens is that many adults do not want to “fool with” the young people most at risk. “They give up too quick on kids because kids haven’t been taught how to have inspiration that they need without somebody pushing them,” Knight said. “(The cycle) starts at home. If you don’t have a parent that has taught you how to understand and how to correct mistakes, you’re not going to know how to do that on your own.”

Society is quick to write off young men such as Knight, he says, because they don’t know what they don’t know. “People don’t want to deal with us as adolescents, or incorrigible adolescents, because we weren’t taught how to do this, how to do that, how to accept that,” he said. “A lot of us being black kids we don’t know how to accept criticism because some of us come up in a house criticized all your life. You was told you not going to be this, you’re not going to be that, so we don’t know how to respond to something that’s not negative, so some (we see) positiveness, we don’t know how to act.”

“It all comes from teaching, from educating each other,” Knight said.

Also see: Solutions to ‘Heartbreaking Violence’: How to Stop the Cycle

To hear more about youth crime and John Knight’s experience as a juvenile in prison, listen to YMP students interview him in the podcast below.

[soundcloud id=’336108827′ height=’false’]

Group 3 of the summer 2017 Youth Media Project produced this package on youth-crime prevention. They are planning a series of public, youth-led forums in every ward in Jackson, culminating in a youth-crime summit in spring 2017. If you want to get involved or sponsor their crime-prevention project, email info@youthmediaproject.com.