By Allyson Knight, Levi Horton, Maurice Hunter Jr., Zariah Wheat and Zaniyah Clayborne

JACKSON, Miss.— In 2022, then-11th-grader Zaniyah Clayborne transferred to Lanier High School from another school in the Jackson Public School District. The school placed her into five AP classes including U.S. History, English Language and Composition, Music Theory, Art History and Biology.

She discovered that a few of the teachers did not know how to teach these rigorous classes, which provide students with the opportunity to earn college credit through an end-of-year examination administered by the College Board, which oversees both the Advanced Placement program and the SAT. Clayborne believes that the teachers gave the students “busy work” to pass the time. “We all left some classes with a 100 average, even though we hadn’t done any work all term,” said Clayborne, a 2023 Mississippi Youth Media Project participant as well as a reporter for this piece.

This was one of the teachers’ first years in a classroom. “She didn’t know how to teach in a class; the students’ test grades suffered because of that,” Clayborne said, adding that the educator didn’t prepare the students for their Advanced Placement final exam at the end of the year. Simply enrolling in an AP course and sitting for the exam is not sufficient to earn students the college credit offered through Advanced Placement, as students must secure a passing score on these standardized tests in order to qualify for college credit.

The educator was a “new, fun teacher,” so not many students informed the administration about the problem, Clayborne said. On some days, the students would walk into her small classroom, put their phones in the blue pocket chart behind the door, sit at their assigned desk and start taking notes off the interactive SMART board.

“She wouldn’t even really explain what we were writing,” Clayborne said.

Throughout the school year, the teacher gave the students assignments, tests and projects but without adequate time, materials or information to prepare, the students were unready for the AP test in May, Clayborne said. Her impression was that the teacher did not understand that every student learns differently.

“She expected everyone to automatically understand what she had ‘taught’ us,” Clayborne said. “We all gave her the benefit of the doubt because she was teaching an AP class in her first year of teaching.”

The art classroom was on the second floor of the school. The walls of the classroom were dark blue and covered with students’ artwork. Former students had painted the ceiling tiles. It was a fun place. “The teacher was really nice, and if you showed up when you were supposed to and didn’t cause trouble, you were fine,” Clayborne said.

The students rarely did classwork because the teacher often had to do art projects for the school, so she didn’t have time to find assignments that would help the students pass their AP test. “What should have been a three hour-long test was over in less than 30 minutes because no one knew what they were even looking at,” Clayborne said.

The lack of qualified teachers in certain districts and in economically challenged communities and towns is an obvious example of educational inequity in Mississippi. Some public schools in more affluent communities can afford and retain better and more experienced teachers, while others cannot. That means their students may get a poorer education and fewer opportunities.

“In one of my classes, a lot of students had not taken the prerequisite class needed to understand the more advanced stuff on the test,” Clayborne said.

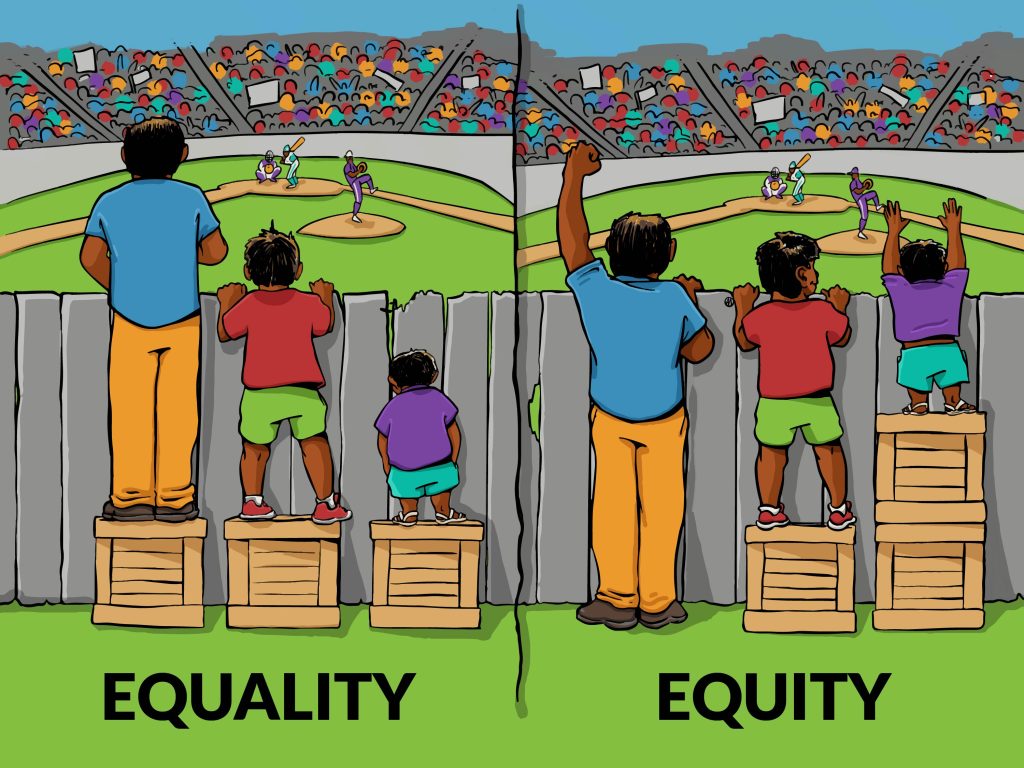

Equity vs. Equality

Equity is not the same thing as “equality.”Advocates for quality education and preparedness point out that providing an equal amount of resources—when that happens—does not mean students will get an equitable education and leave prepared for higher education or the workplace.

“Equality requires that everyone receives the same resources and opportunities, regardless of circumstances and despite any inherent advantages or disadvantages that apply to certain groups,” the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which focuses its philanthropy on children and families, explains on its website. “Equity, on the other hand, considers the specific needs or circumstances of person or group and provides the types of resources needed to be successful.

Equity is not one-amount-fits-all. “Educational equity is when all students—regardless of their socio-economic background or geographic where-abouts—have opportunities to learn and grow with resources specifically tailored to them,” Teen Life Coach Tonja Murphy of Jackson told the Youth Media Project.

“Within equity, one set of students might need a specific thing, whilst another set of students might need something completely different,” she continued. “Depending on where they are, they could be two totally different things, so when deciding if something is equitable you can’t say, ‘I gave you the same thing, so why are you struggling?’ It’s not the same thing.”

Murphy, a published author, a life coach for teenagers and the community engagement coordinator for the Mississippi Book Festival, grew up in Jackson, Miss., and graduated from Murrah High School. She went on to attend Hinds Community College and then Jackson State University.

“When it comes to equity you want to make sure that students have access to what it is they need so they can be successful,” Murphy added.

What students need depends on what they already have. Equality in education means giving each student the exact same resources no matter their needs, whether it’s time, money or other supplies for the class. Equity means that each student receives exactly what they need in order to succeed, even if it’s “more” or “less” than what another student needs or receives. Those opportunities can be missing for a variety of reasons, including poverty, race/ethnicity and other factors, all of which have historically led to fewer resources for certain children.

SmartLab reports that an equitable school environment for teachers, students and other staff members will ensure that everyone has what they require to succeed by personalizing learning, teaching and administering to the population’s specific needs.

Equitable schools work to provide a strong educational landscape where each student’s needs are met, academically and socially, and to create a safe and positive learning space for students to feel comfortable learning and maintaining the skills they need for life.

Ultimately, educational equity means the ability to increase resources and income in order to keep the cycle from repeating for future generations. It is better than it used to be—decades ago, many young people suffered from being blocked outright from segregated schools. That had far-reaching effects.

“Inequity in education has increased income inequality in America,” reporter Kimberly Amadeo wrote in 2021 for The Balance. “Over a lifetime, workers with college degrees earn 84% more than those with only high-school diplomas, Meanwhile, those with master’s degrees or higher earn 131% more than high-school graduates.”

Still, schools and experiences such as Clayborne’s in Mississippi schools show how necessary both equity and equality are in ensuring that all young people have the resources they need for a good education and to break inequitable cycles.

How Inequity Manifests in Schools

Education leaders in Mississippi acknowledge that inequity causes inadequate instruction and results in fewer properly trained teachers who are able to provide the same level of instruction to all students.

“Few staff can impact a student’s education,” Dr. Michael Cormack Jr. told YMP in July 2023. “Staffing is very essential because our district is only as strong as our principals, teachers and leaders allow it to be.”

Cormack has been working in education for 21 years, beginning his teaching career in Indianola, Miss., in 2003 before going on to become the CEO of the Barksdale Reading Institute, which closed in 2022. He is now the deputy superintendent for Jackson Public Schools.

“Teacher shortages are real and cyclical,” he said. “The Delta is losing population, and many rural parts of Mississippi are losing population because it is hard to attract people back to less fortunate communities.”

The Iowa native, who ended up in Mississippi through Teach for America, recalled the barbecues he hosted at his home to create more of a familial atmosphere in the community that, in turn, increased education quality. This community-oriented mindset helps neighbors and parents create a better environment to together make positive advancements.

“Great education is about educators, principals and district leadership centering the students,” Murphy said. “Ways we can promote equity in our schools is by making sure we keep the student at the center of everything we do.”

Equity Takes A Village

When making decisions for students, educators must “keep in mind what’s best for them and make sure that we aren’t doing anything that would harm them,” Tonja Murphy said. “Allowing students to be a part of the big decisions will not only affect them, but it ensures all students are worth listening to and that their voices are being heard.”

Murphy said letting students see that adults can work together promotes equity in schools.

“Seeing that school staff and parents can work together has positive effects on the students,” Murphy said. “The parents being a part of decisions for their students allows for the parents to be more involved in how their children are doing and how they can help.”

“Creating equitable learning environments requires active listening,” Cormack added.

It is vital to not just focus on the negative about public schools but to also celebrate the positive in order to build equitable environments for learning rather than treating public education like a death spiral, experts advise.

“(By) sharing what we do well, what we could do better and being open to feedback, it also displays how the school district is actively working toward a goal,” Murphy said.

Posting photos and videos, rewarding students, keeping families up to date, and putting work and progress on websites allows other schools and community members to see what is being done well.

“Still, money matters,” Cormack warned. “Schools with mostly students of color are still struggling with getting the right amount of resources they need to have a quality education. Education equity has come a long way, but there are still things that can be done to improve the lives of students, parents and staff having to deal with these problems all school year.”

‘With All Deliberate Speed’: Historic Obstacles to Equity

School equity was at the very heart of the Civil Rights Movement and its goals. Activists and Black lawyers like Thurgood Marshall focused on removing institutional barriers to racial equality in education, which had been in place since the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of legally enforced Jim Crow segregation. Even after the violent fight to stop Black children from attending school finally lost, the racist, inequitable distribution of resources helped white children at whites-only schools enjoy the benefits of a better-funded education for decades.

In 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the ruling on the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case challenging school segregation. The decision overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine, and schools were expected to integrate “with all deliberate speed.”

But change was still slow. The Brown ruling provoked more resistance, often violent, from white people. For 16 years, racist white Mississippians resisted integration of school districts. In September 1962, then-Gov. Ross Barnett spoke during halftime at a University of Mississippi football game against the University of Kentucky.

In his infamous “I Love Mississippi” speech at Memorial Stadium in Jackson on Sept 29, 1962, Barnett riled up the people in the Confederate flag-filled bleachers. The next day a riot took place on the Oxford campus against the enrollment of James Meredith, the first Black student at the University of Mississippi, which still embraces the nickname “Ole Miss,” taken from the nickname of slave owners’ wives.

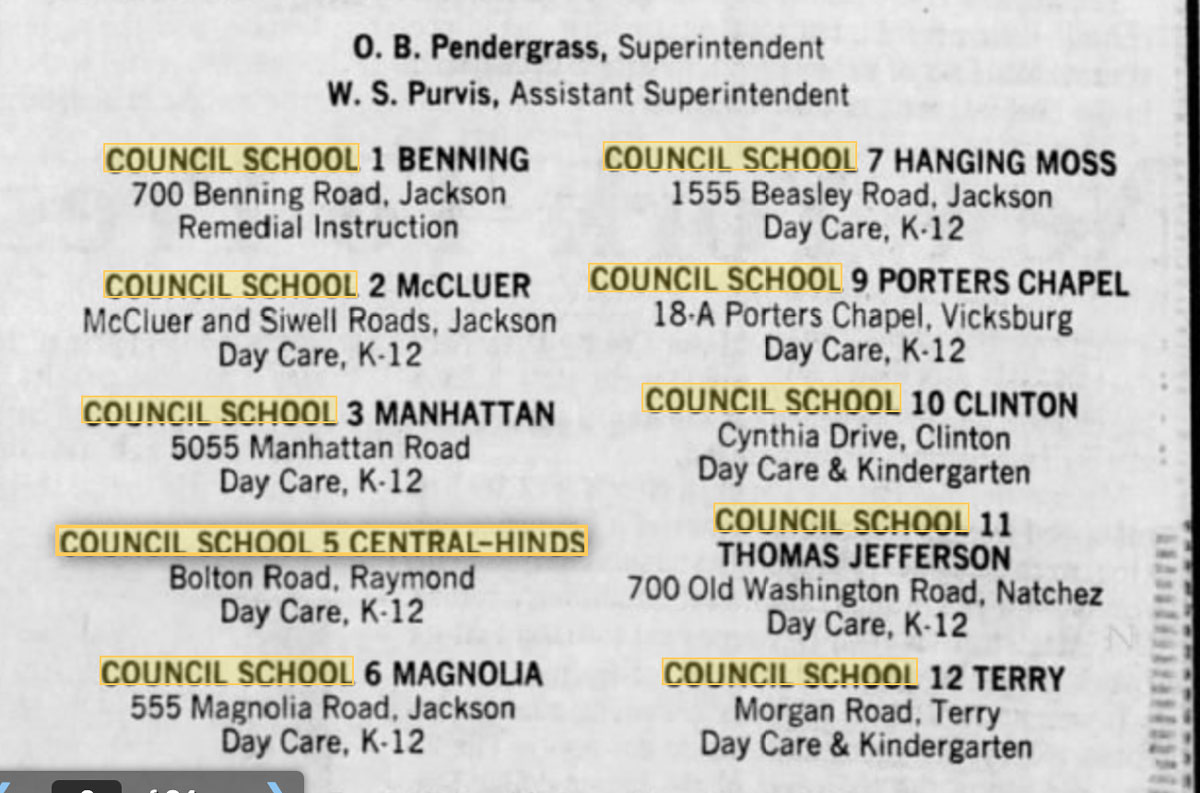

By the 1960s, state leaders started providing more money to Black schools—although still not as much—in order to keep the schools separate and to avoid legal battles due to differences in funding. They also set up whites-only segregation academies that also used public funding until courts later stopped it. (Some leaders still support “vouchers” of tax money for private schools—a practice that started in the early 1960s to help white families choosing segregation academies to afford private school tuition in order to avoid integration.)

The damage was done, meaning that the Brown v. Board decision was the beginning of school resegregation and massive white flight out of cities like Jackson, resulting in the growth of segregation academies and better-funded public schools in whiter suburbs. That meant that cycles of inequity continued in many schools in poorer neighborhoods with lower property values. Poorer education and college and workplace preparation due to inequity, in turn, helps keep those neighborhoods struggling with fewer property-tax dollars at their disposal.

The Brown decision wasn’t enforced in much of the South until another Supreme Court decision in late 1969 demanded that districts integrate immediately, which opened the floodgates on white flight from schools in Jackson and beyond, as well as growth of many white academies.

“Continued operation of racially segregated schools under the standard of ‘all deliberate speed’ is no longer constitutionally permissible,” the court wrote. “School districts must immediately terminate dual school systems based on race and operate only unitary school systems.”

Still Inequity Decades After Brown Decision

Nearly seven decades after the Brown decision, increases in funding and multiple court wins to stop segregated schools and resources, Mississippi schools still suffer from inequity.

One major reason is the white flight both to the suburbs and to segregation academies that opened immediately after the U.S. Supreme Court told hold-out public-school districts to integrate in early 1970. Since that time, many formerly all-white public schools in Jackson have shifted to majority-Black and have suffered from low resources due to the white tax base fleeing the capital city to avoid school integration.

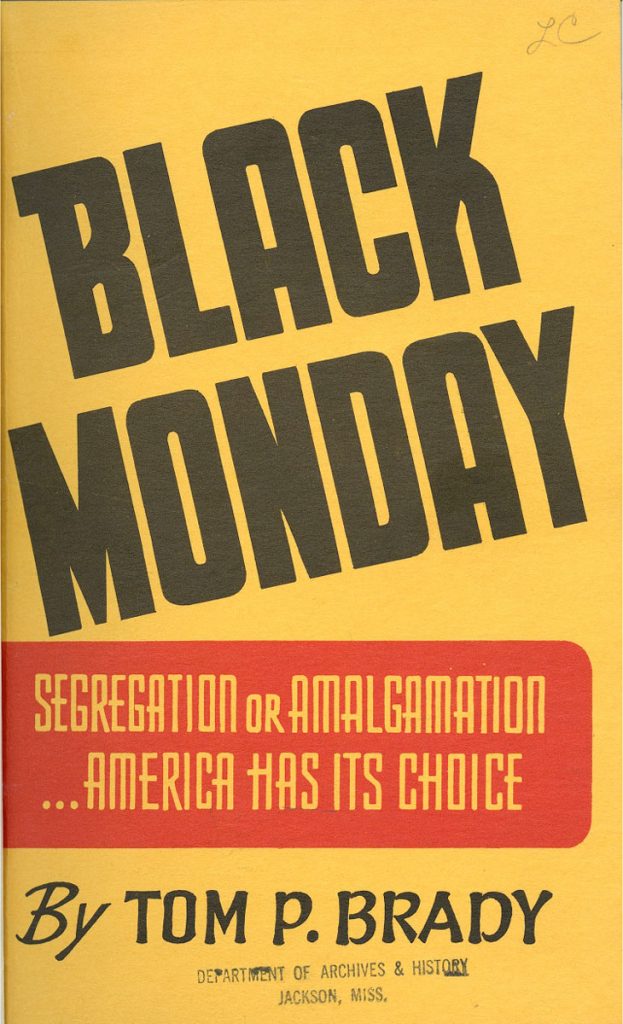

The impacts of the decades-long pushback on the 1954 Brown decision continue even today. Former Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Tom P. Brady of Brookhaven helped build resistance in his May 1954 “Black Monday” speech following the Brown decision. The prominent judge compared Black people to apes while encouraging many white leaders to join the White Citizens’ Council, which perpetuated the lie that Black people were inferior to whites, even as it started multiple Council schools in and near Jackson.

The Black Monday speech was later printed in a booklet that was given to white schoolchildren. It contained legal documents, ideas about eliminating the NAACP, information about creating a new state for African Americans and reasons why segregation supposedly led to a “structured” society.

Lawyers used Brady’s racist arguments in court cases in Jackson against Black parents suing racist leaders to allow their children to attend well-resourced public schools all over Jackson, even arguing that Black children weren’t able to learn as well as white children due to their race.

Brady’s work to get white southerners to aid in the effort to stop integration did not stop the legal end of segregated schools but manifested into shrinking resources for schools that would become majority-Black as white families fled.

Many white Mississippians actively worked—and still work—to avoideven “adequate” public-school funding in Mississippi, despite some legislative efforts to bring equity to school funding. Mississippi’s public-education system is funded largely by a mixture of state funds and money from local property taxes, which bakes in inequity, given that such resources benefit students in wealthier areas and neighborhoods more. That privilege manifests in many differences from teacher quality and retention, to facility quality and maintenance, to safety and security, to classes and extracurricular activities offered—even within the same district.

At the Youth Media Project in summer 2023, students in public schools throughout the Jackson metropolitan area learned that they do not have the same access to learning and extracurricular options from taking Spanish classes to holding homecoming events.

“I never realized how little JPS had compared to Pearl or Madison,” Taylar Fakes, a student journalist for the Youth Media Project, said.

Jackson Public Schools Is Shrinking

Deputy Superintendent Cormack said Jackson Public Schools had 30,000 students just over a decade ago, which is now down to about 19,000 as the population of Jackson continues to decrease. The capital city has lost about a quarter of its residents since the 1970s.

The Jackson Public School District has about the same number of students right now as the Rankin County School District but has far more buildings.

“For the same student enrollment, Rankin County has 28 school buildings, while JPS has 52,” Cormack said.

The extra buildings can be expensive to maintain—and they resulted from the need to support separate segregated schools. “For the same number of students in Jackson in particular, twice as many things were built as needed because the city wasn’t committed to Black and white students going to school together,” Cormack said of Jackson’s once-all-white elected officials. “All of this infrastructure is based on a legacy of racism and segregation.”

Several schools in the district have closed because their neighborhoods no longer have a strong population to support them. Cormack said that bringing Hardy and Blackburn middle schools together in 2020 helped improve teaching and learning. The population at the schools and in the neighborhood surrounding Hardy was declining, and there weren’t enough students to keep the school open. Hardy Middle School was consolidated into Blackburn, and the Hardy building will become an athletic facility.

Hardy did not have enough teachers, and some of the teachers they did have were not fully qualified to teach certain subjects, Cormack said. The teachers at Hardy had overcrowded classrooms because there were not enough teachers for every class to be a normal size. Combining the schools gave the students from Hardy the same opportunities as the students from Blackburn.

“We were able to realize these improvements in teaching and learning just by bringing these two middle schools together. And that’s what happened, right? We didn’t have overcrowded classrooms.” Cormack said.

In 2023, Brinkley Middle School merged with Lanier High School for similar reasons, Mississippi Free Press education equity reporter Torsheta Jackson wrote. Jackson is also a mentor for the Mississippi Youth Media Project.

Students Fund Public Schools in Mississippi

The Public School Finance Programs of the United States reports student enrollment determines how much funding the 1,050 public schools in Mississippi receive. The State of Mississippi currently pays public schools the same amount for each individual student’s education regardless of the conditions of the school or the community around it—around $5,000 as of summer 2023. In nearby states such as Louisiana and Alabama, the state pays around $12,000 per pupil. Mississippi has the 34th-largest school system in the country with more than 400,000 students enrolled for the 2023-2024 school year.

Small schools and districts have it easier due to fewer students to serve. Shaquibia Carter, a public-school assistant principal at Raymond High School, said her facility is a small 534-student school within a small community. That means it can have several different types of classes to help prepare students for their future lives and higher education.

“They have a personal connection with their students,” Carter said. “That’s what makes them different.”

Charter schools also can offer options for students that larger public schools often cannot even as they avoid some public-school obligations while using public funds. “Charter schools are public schools of choice that operate with autonomy from many of the regulations that apply to traditional public schools,” the Mississippi Department of Education explains online.

As of summer 2023 in Mississippi, 3,000 students attend the 12 charter schools across the state of Mississippi with state funding of $6,000 per student.

Kevin Parkinson, principal of Midtown Public Charter School (4th to 8th grade), has more than 200 students and offers several extra classes for each student that are not offered at all Jackson public schools. These extra classes include Spanish, coding and art.

Midtown Public Charter school is an alternative choice for a small percentage of Jackson’s young people. The Midtown admissions standards are similar to regular public schools, but you have to apply for your child before spots fill up. Parkinson says his school is always looking for new opportunities to improve their school. Public charter schools do not have a public board; they have mostly private boards while using public money and have some “flexibility around the rules,” Parkinson said.

Integration at Its Finest

Dick Molpus, a former Mississippi secretary of state from Philadelphia, Miss., and a long-time critic of both charter schools and private academies, was a senior in high school when the U.S. Supreme Court forced schools to finally integrate in 1970. Black people had already been given a “freedom of choice” to integrate in some Mississippi areas as a way to claim equality while trying to fend off fully forced integration, but most Black families didn’t because of fear of violence.

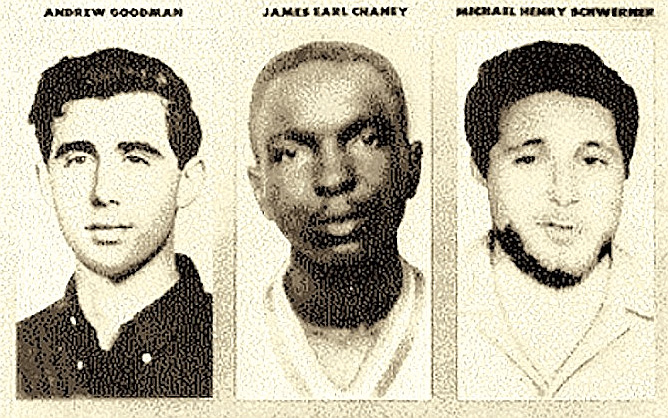

Right in Molpus’ hometown, local law enforcement and Ku Klux Klansmen burned a Black church where people were trying to register to vote and then killed three civil-rights workers in 1964 who were there to help with voter registration and who were working for education equity, including by running their own Freedom Schools.

As secretary of state, Molpus apologized to the families of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner—an apology later believed to help opponent Kirk Fordice defeat him for governor.

“When leaders didn’t stand up and how they let the bullies roam and burn people’s lives, that’s what really changed me,” Molpus told the Youth Media Project student journalists.

Molpus, who founded Parents for Public Schools in 1991, has since fixated on the need for education equity starting with a level of public-school funding that allows majority-Black schools to enjoy the same level of resources and opportunities as white, suburban schools.

But that effort has been an uphill battle. “The inequity between the have and the have-nots is continuing to happen in public schools in Mississippi,” Molpus said.

That equity started with young children, Molpus and his equity-seeking colleagues believe.

Molpus, along with other young adults, worked with then-Gov. William Winter, who became known as Mississippi’s “education governor” after shifting his views on segregation and dedicating much of his life to educational equity and working to reduce racism.

While in office, Gov. Winter passed educational initiatives that helped improve Mississippi education. Molpus and other younger Mississippians dubbed the “Boys of Spring” helped their boss lobby the Legislature to fund kindergarten for all public schools, to mandate school attendance, and other reforms to help alleviate the outcomes of long-time poverty and illiteracy.

That was a major step forward for education equity in Mississippi, but efforts by Molpus and others to convince Mississippi leaders and legislators to follow state law and fully fund the Mississippi Adequate Education Program—designed to help poorer districts—has not found consistent success.

However, the 2023 Mississippi Legislature, in an election year, voted on House Bill 1613, which increased funds for public schools and colleges in Mississippi.

“When I first got elected, there was no state-funded Pre-K,” state Sen. David Blount said in summer 2023. “We increased funding for Pre-K in Mississippi and community college.”

The Mississippi Legislature passed the Winter-Reed Teacher Loan Repayment Program in the 2023 session to help decrease the state’s teacher shortage. The State of Mississippi will repay part of new teachers’ student loans for three years.

“If you go and become a teacher the state is going to help repay some of your loans, and if you come to a district like Jackson, it has a shortage in teachers. We’re going to pay you a little bit more money,” Blount said.

Still, teacher pay in Mississippi was one of the lowest in the country as of summer 2023. The World Population Review reports that, as of summer 2023, Mississippi teachers made around $47,000 a year, while in surrounding states such as Alabama, teachers earned around $55,000 a year. The national average of teacher salaries is $68,469 a year. That number falls between Mississippi’s $47,000 and Massachusetts’ $92,000 from the 2022-2023 school year, We Are Teachers reported in 2023.

“So what the legislation needs to do, in my opinion, is fully fund the school districts and then they decide how that money is spent with regard to teachers,” Blount said.

Solutions for Inequity in Schools

The Mississippi Department of Education took on the issue of inequity in education in 2015, creating an 82-page plan to “Ensure Equitable Access to Excellent Educators.” The Mississippi Education Equity Plan called for collaboration with the districts to create requirements for new qualified teachers, supporting teachers and culture competencies training. The goal was to provide trainees with the “tools needed to help effectively interact with people of different cultures in a way that is respectful, responsible, and sensitive to their linguistic needs.”

Then MDE said after these three plans are implanted, that “Mississippi school districts will decrease the rate at which high poverty and minority students are taught by inexperienced and inappropriately licensed teachers, increasing equitable access for all students.”

“There are some teachers who are not qualified to teach, but they are teaching students anyway,” Cormack told the Youth Media Project.

But not only teachers and administrators are responsible for solutions, education experts emphasized to the Youth Media Project.

“Through the mix of it all we have to keep our students in the center of decision making,” Tonja Murphy said. Former JPS educator Terry Hunt agreed, saying students play an important part in demanding more equitable education options.

“Education inequity can be solved in Mississippi schools by allowing students to use their voices and not staying silent,” Hunt, the wife of Molpus, said. “We cannot give our power away.”

Hunt emphasized that students should help teachers feel appreciated everyday.

“Teachers are human, too,” she added.

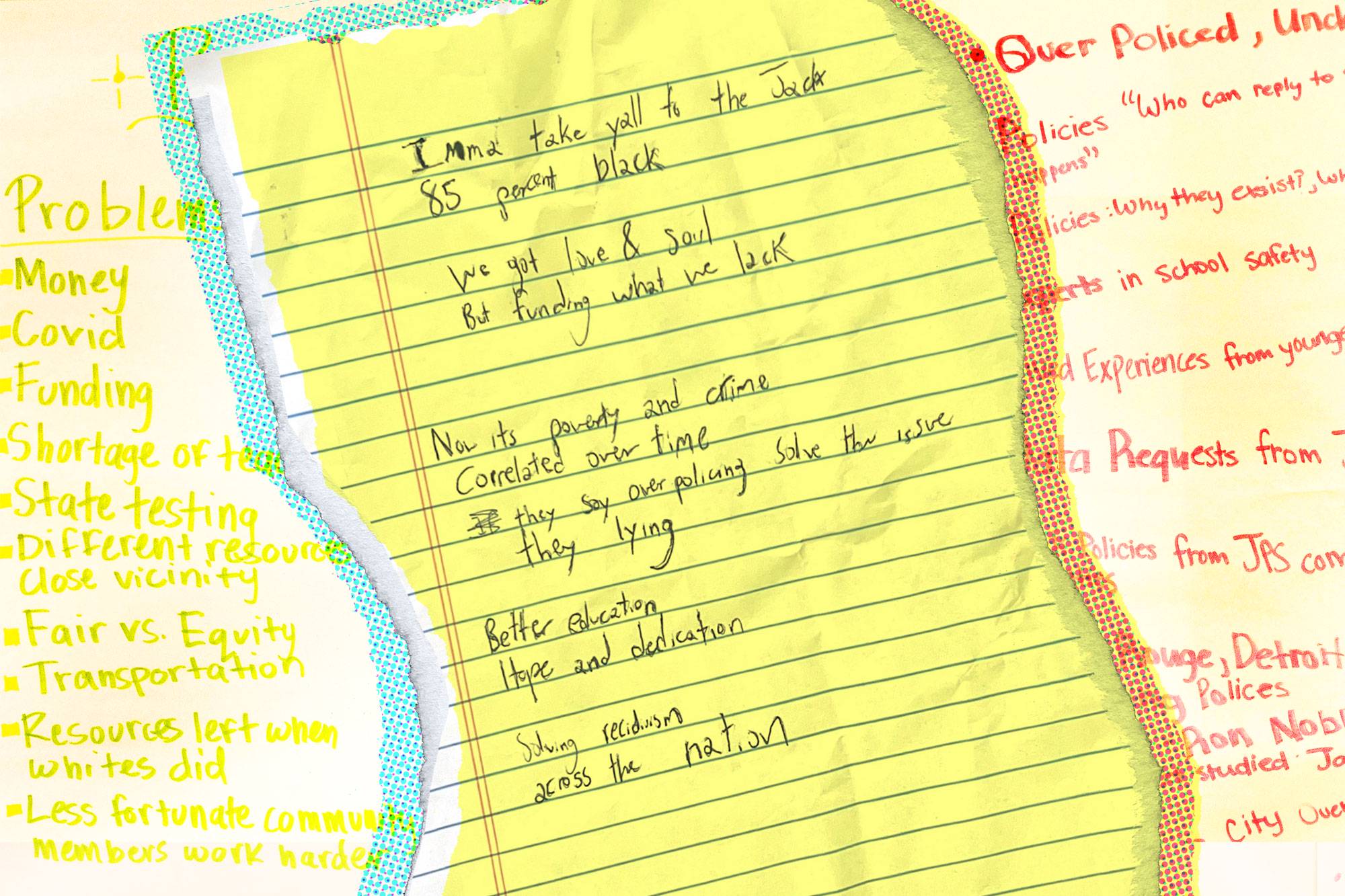

The Youth Media Project’s Education Summer program allowed students to take a closer look at the problems within school districts in Mississippi, connect the equity dots through brainstorming and a systems analysis of what can be done to solve those problems and find additional resources and then use them well and equitably. Working in groups and interviewing a variety of experts has allowed students to focus on inequity that directly affects them. YMP teeangers believe allowing the students to be a part of decisions and solution-seeking that will directly affect their school experience and outcome will be beneficial to full communities in the long run.