By Kirstyn Lyles, Kaitlyn Poole, McKenzie Matthews, Zaniyah Clayborne

In 1984, there were no African American female legislators in the state of Mississippi—until Alyce Clarke took office. Alyce Clarke, now 85, retired from public service in January 2024 after serving as the first Black woman legislator for Mississippi, eventually spending 38 years in the Capitol. While in office, she advocated for the rights of women and children, food programs, setting up drug courts and funding school breakfasts. She also founded the Women’s Caucus in the Mississippi House of Representatives.

Clarke worked for the Mississippi Legislature for four years before she was offered a key to a bathroom that had previously been whites-only. When Diana Peranich was elected in 1988, House Speaker House Speaker C.B. “Buddie” Newman sent a security guard to give her a key to the bathroom.

The state’s first Black woman legislator got home and told her husband that there was a bathroom for white women that she had never known about. Her husband said they should tell the media. “He was kinda mean, so I said to myself, ‘Looks like I need to tell them,’” Clarke told a Youth Media Project reporting crew in her Jackson home.

Clarke called the media and told them the whole story. “They couldn’t believe it,” she said. The next day, when the legislator walked into the Capitol, the security guard met her with a key to the bathroom as soon as she walked through the door. “I’ve been here all this time and haven’t had one. I don’t need one now,” she told him.

The security guard went to Newman and told him that Rep. Clarke wouldn’t take the key. She was called into the Speaker’s office, and the speaker said: “If you take this key to the bathroom, we will start working on a bathroom for women today, and we will make you chairman of the committee. You ain’t been here 15 minutes, and we are going to make you chairman.”

Newman offered her the chairman position with the hope that she wouldn’t tell the media. She told the speaker the difficult truth: “I promise not to tell them, because I told them last night.”

History of Women Getting the Right to Vote

In ancient societies, women were often considered the property of their fathers or husbands. They had limited legal rights and were largely excluded from political and social life. The year 1848 marked the start of the women’s movement in the United States. In July that year, the Seneca Falls Convention in New York became a significant turning point for American women. Organized by suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott Jane Hunt, Mary M’Clintock and Martha Coffin Wright, it was the first woman’s rights convention and produced the Declaration of Sentiments, which called for equal rights for women, including the right to vote—but not for all women.

Stanton, along with Black leader Frederick Douglass, gave passionate speeches at the convention emphasizing the 11 resolutions on women’s rights. Three years later in 1851, Stanton met suffragette Susan B. Anthony at an anti-slavery meeting. Together, they started the National Woman’s Suffrage Association in 1869. In that same year, Lucy Stone and Julie Ward Howe founded the American Woman’s Suffrage Association.

In 1878, Aaron A. Sargent, a California senator, introduced the amendment to grant women the right to vote in the 38 states. Sargent died in 1887, 42 years before his proposed amendment would be ratified. The 19th Amendment—which granted women the right to vote—was ratified in 1920, but the Mississippi Legislature chose not to ratify the 19th amendment in March 1920, although it passed without the support of the southern state. Sixty-four years later, the Mississippi Legislature finally voted to ratify the 19th amendment.

Although women were granted the right to vote, many Black women, particularly in the South, faced significant barriers due to discriminatory practices like literacy tests, poll taxes and other measures of voter suppression. Despite possessing the legal right to vote, Black women were often subjected to intimidation and violence when they attempted to register and cast ballots. It wasn’t until the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that the discriminatory practices were officially abolished, allowing Black women to begin to fully exercise their right to vote.

This period also saw women entering the workforce, particularly during World War II when they took on roles traditionally held by men. The mid-20th century was marked by the second wave of feminism, which focused on issues such as reproductive rights, workplace equality and legal inequalities. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 included Title IX, prohibiting employment discrimination. The 1970s saw the rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement, advocating for broader social and political changes, such as the ratification of the failed Equal Rights Amendment.

Today, the fight for women’s rights continues to evolve. Issues such as gender-based violence, reproductive rights and workplace equality remain central. The #MeToo movement that started in 2017 brought about global attention to widespread sexual harassment and assault. This movement helped lead to significant social and legal changes., though women continue to face numerous challenges, including disparities in pay, representation in leadership roles and access to healthcare.

Women’s Health: Rights Not Guaranteed

Attorney Vara Lyons, a former policy council for the American Civil Liberties Union and a former board member of Faith in Women, a reproductive-rights nonprofit that focuses on access to abortion care and supports pro-choice clergy members, has much to say about women’s rights in health care—and especially reproductive care, which is on the national ballot in November.

“I think (men are) meddling with an area that they don’t need to meddle with,” Lyons said. “These people are not physicians. These men are making decisions that they have absolutely no education about.”

Politicians and government officials in Mississippi have not expanded Medicaid despite efforts to do so, including Rep. Missy McGee’s push for expanded health care during this past legislative session. McGee is a Republican state representative from Hattiesburg who introduced the “Postpartum Care Extension Act” (House Bill 413) in the 2022 Mississippi legislative session, aiming to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage for new mothers from 60 days to 12 months.

The bill also had many other provisions, such as an offer of coverage for mental-health services and access to necessary medications and medical equipment. The refusal to expand Medicaid has resulted in the state forfeiting billions of dollars in federal funding. Reasons for the inaction include opposition from Gov. Tate Reeves and former Gov. Phil Bryant and concerns about the costs, despite the federal government covering at least 90% of expansion costs.

Of his refusal to expand Medicaid coverage in Mississippi, Gov. Reeves said, “I believe that Medicaid expansion would create a culture of dependency and decrease the incentive for people to work.”

A lack of expansion of Medicaid means that women in Mississippi and other non-expansion states face significant barriers to health-care access. “I think it’s really cruel,” Lyons said. “It boggles my mind that you can sit there and look at the statistics that we have in Mississippi, especially for maternal mortality and healthcare outcomes, and refuse to do something about the problem at hand simply for political talking points.”

The closure of hospitals in Mississippi that has resulted from the failure to expand Medicaid has significant implications for women’s health and well-being, she said. The lack of expanded health-care funding has created a decrease in pay and a decrease in the amount of money being put into hospitals, exacerbating the closure of hospitals.

“From a policy standpoint, I think that the fact that there are hospitals closing in Mississippi is a big restriction on maternal and fetal health,” Shernica Ferguson, a researcher with a master’s in public health, said. “Also, as a member of a marginalized group, that poses more barriers against me because of the disparities and social inequalities that happen in health care.”

In addition to rampant hospital closures, Mississippi has been at the forefront of restrictions on reproductive health-care services, particularly abortion. In 2020, the state passed the Gestational Age Act, which bans abortions after the detection of a fetal heartbeat—which often occurs before many people know they’re pregnant. This law only allows exceptions in cases of rape or when the pregnancy puts the person’s life in danger.

Since the passage of that law, Mississippi has continued to cut funding for reproductive health-care services. “We need more abortion funding because we have women that are forced to drive out of state, they’ve got to get child care, and a lot of people have to pay out of pocket,” Lyons said. “About half of abortions are paid for out of pocket.With the current state of the economy, you’re looking at paying at least $500 for the procedure, plus you’ve got to get child care, plus if the state has a rule about waiting 24 hours, you’ve got to stay in a hotel. And Medicaid, typically, doesn’t cover abortion access because of the Hyde Amendment.”

The intersection of education and politics in women’s health care can have significant consequences for women’s access to quality care, autonomy and overall well-being. Mississippi legislators have thus far refused to mandate comprehensive sex education in schools and by cutting funding for programs that provide reproductive health education and resources.

“Another thing I would spend more funding on is teen contraceptive education, because Mississippi does not have standardized sexual health education in place. They favor an abstinence-only model, and we have the highest teen pregnancy rate,” Lyons said. “So the other thing that kind of boggles my mind with conservatives is that they say they want to protect babies. Well we’re not even doing anything to prevent babies being made in the first place.”

Former Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant is anti-abortion and supported the failed Personhood initiative in the state in 2016. “Republicans are often criticized as only being concerned with children who are in the womb. One of the things that we’re trying to do is to make sure that we take care of the child after birth,” he said.

In fact, it has been an uphill battle in Mississippi to help extend Medicaid insurance for 60 days after a woman gives birth here—a very dangerous time. “Postpartum is a dangerous period for Mississippians. Of all maternal mortality deaths specifically tied to pregnancy complications, 86% happen postpartum, compared to about one-third nationally. More Mississippi moms are dying in this postpartum period than nearly anywhere else in the U.S.,” the Mississippi Free Press reported in April 2021 after the state Legislature killed the 60-day extension bill.

But a year later, it finally passed, and Gov. Reeves signed it into law.

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Women’s Rights

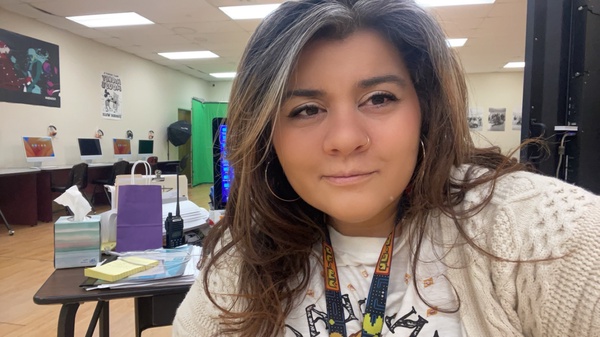

At Terry High School, Noor Atarji’s classroom had a simple layout: two rows of computers for her students to use in their work, a green screen, tripods and cameras for filming videos. Her class mainly focused on photography, video editing and other skills that would be useful to students aiming to enter the graphic design field.

Atarji, a career and technical education, or CTE, teacher for the Hinds County School District, operated her classroom like a studio before she was alerted that certain parts of the way she taught had to be changed. “I have recently found out that the State of Mississippi has actually changed the curriculum for digital media,” she said. “Now, the state wants me to incorporate AI into my teaching.”

Over the summer, she has been experimenting with using artificial intelligence to create certain artwork, but she feels conflicted on whether it is a positive or negative tool in many spaces. “I think it all depends on the context that it is used,” she says. “I’ve been playing around with AI a little bit. Just trying to figure it out. Like, what is this all about? You know, how does it work?”

For an artist, it is hard for a computer to create an image that caters specifically to their ideal vision, but Atarji believes that it can be useful in providing inspiration for an artist to incorporate different elements of the generated image into their own pieces.

Atarji believes that there should be a limit to the use of artificial intelligence when it concerns real people, and this is especially pertinent for women. While many people push the good of AI, there have been negative aspects for women—normally in the form of explicit photos or deepfakes. Deepfakes are digitized videos that take a real person and use AI to map the person’s images to make them perform certain actions.

“I was in a leadership meeting, and we were talking about AI, and that was one of the things that was brought up–how dangerous it can be in that respect,” Atarji said. “A lot of women feel—and in a lot of ways are—being violated.”

Because artificial intelligence is constantly learning, Atarji is hesitant to fully incorporate it in her classroom. “It’s disturbing, and I think that’s where my apprehension lies in using it,” she says. “It’s ever-learning and it’s continuously progressing.”

Technology is constantly changing, and society’s reliance on it is growing. Since the early 2020s, AI has found its way into everyday life, typically in the form of animated advertisements and news articles. Some different software types have even incorporated AI into their branding.

Although AI has been around since the middle of the 20th century, it is only now–in an internet-heavy age–where its powers are broadcast for all to see.

There are very few regulations on generative AI, and even fewer on how generative AI affects women. In the past few months alone, there have been multiple cases of people using generative AI to make sexually explicit videos of female celebrities. In October 2023, The White House’s Executive Order on AI was published. In the order, President Biden states that “Artificial intelligence (AI) holds extraordinary potential for both promise and peril.”

For women, especially, the advent of technology in the health-care field has given rise to a massive shift—especially the implementation of artificial intelligence. From having a robot hand out prescriptions to patients to having an artificial doctor visit, the medical profession has embraced AI, even as critics says the risks may outweigh the benefits for women’s health.

Despite the world’s progression into the digital age, the fact remains that women have been fighting for the rights that men have been given since birth for centuries.

Whether it be how generative AI is affecting women or how funding affects women’s health care, women’s rights have been at the forefront of the 2024 election.