By Haley Bradford, Kierra Rand, Ferrari Shakespeare, Ava Washington

Samantha Cross sat at her desk, studying. All they ever seemed to do in the high-school history class was study and write, study and write. “Will I ever get to express my opinion on this?” Cross asked herself.

“All this teacher does is talk. Just sitting here taking notes and reading is getting so repetitive,” Cross thought as they reviewed court cases. Even though history and politics are discussed in school, it doesn’t mean the student will show interest in it—but Cross did.

When she sat in on another class, Cross saw how that teacher engaged with her students: making them get up and move around, having discussions. “This method works,” Cross thought to herself, and she wanted to model it in her own someday-classroom, which she now teaches in herself, using the lessons of her school experiences.

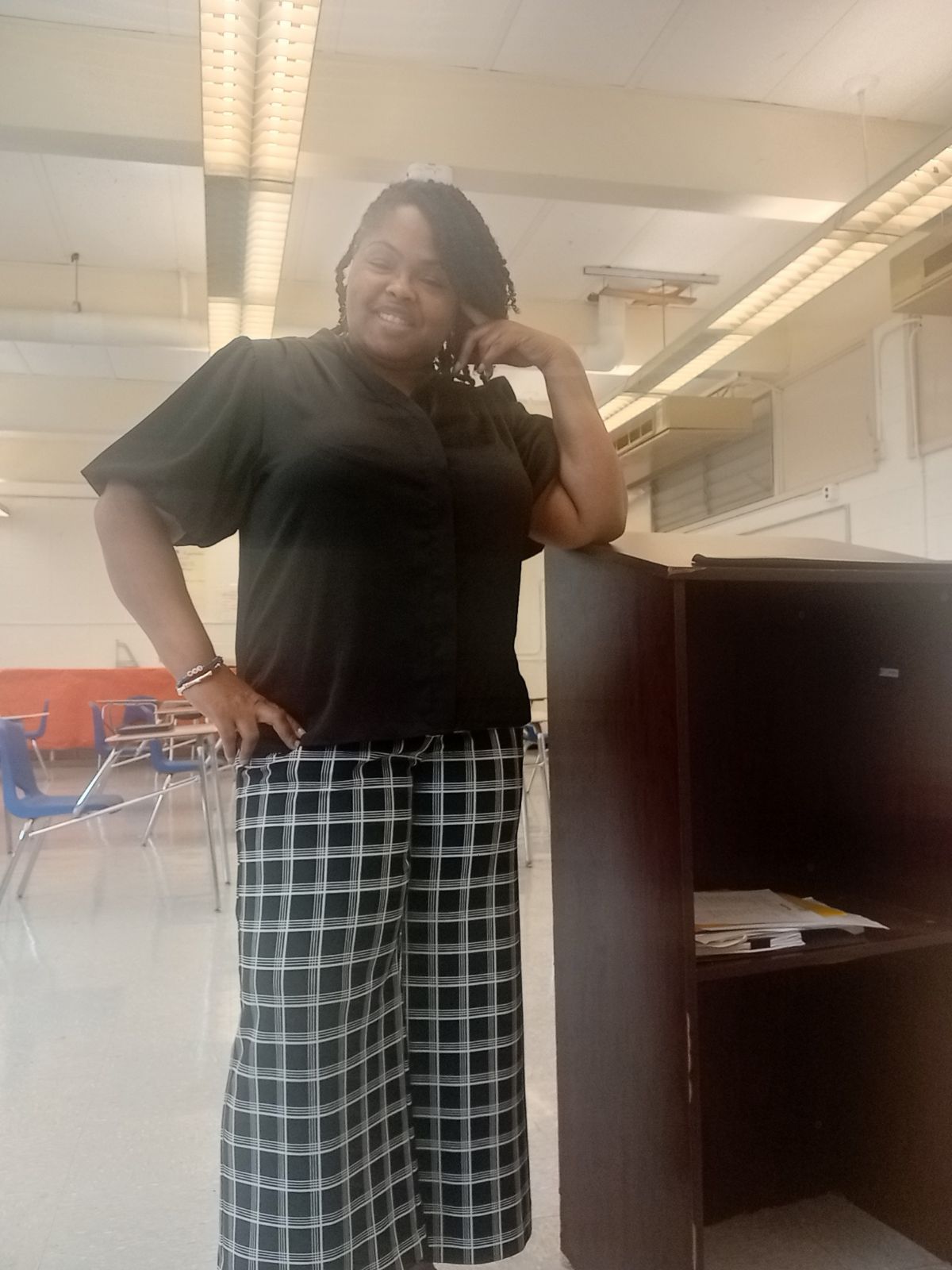

Samantha Cross teaches her students using an open environment to help them better understand her civics lessons. They can express their opinions and add to the discussion, far beyond memorizing facts. Courtesy Samantha Cross

Cross was raised as a “military brat,” always traveling with her parents. Her mother, Lillie Burrell, was a teacher and ensured that her daughter was very educated on her environment’s history. As she was raised in Greenwood, Miss., history was a driving factor for her, particularly Black history. Because Greenwood had many slaves, it was the perfect place for her to study. Her passion to learn more about the past was exceptional, and even at that early point in her life, Cross knew she wanted to become a history teacher.

“I wanted to teach in a different way,” Cross told the Youth Media Project. She didn’t want to subject her students to learning by memorizing facts and dates. It had been proven time and time again that if she did, her students would not fully excel in civics. History meant something to Cross and making her students feel the same was something she aspired to do. To do this, Cross decided to provide her students with an open environment where they could discuss their opinions and beliefs—and it worked.

“The bell has rung, class,” she will say loudly over the chatter of her students at Powell Middle School in Jackson, Miss. But still, they often continue their conversation. In that moment, Cross feels accomplished. She has gotten them so interested in her lesson that they do not want to leave class, but instead prefer to keep talking about their current subject. The class members are sure to remember this feeling of excitement, and so is Cross.

Understanding Vs. Memorization

The methods teachers use to teach students have an impact on how well they learn the content. The open discussion method that Cross applied in the classroom represents understanding. “In most cases, we should rely on actually learning the content instead of trying to memorize it. We should never rely on memorization when we need to apply the information in real-life scenarios or on a test,” Schoolhabits.com advises.

Unlike what Cross applies in the classroom, memorization is the teaching method that she was subjected to when she took history classes. Memorization leads up to information learned to be temporary and limited to basic words and facts. Schoolhabits.com considers memorization to be unconnected to real learning. It has been shown that test scores are affected when using these differing teaching methods.

The results of these teaching methods reflect in test scores. Online Journal of Quality in Higher Education indicates that the outcomes of students taught using the open discussion Cross modeled method versus students taught using the conventional method that Cross experienced in school is markedly different. The hypothesis that “discussion method has no significant effect on the performance of students taught reading comprehension in secondary schools ” was tested—and proved incorrect. The mean scores of students taught using the discussion method was 3.34, while the scores of students taught using the conventional method was 2.92.

Not only does using the discussion method impact test scores to be greater, they also get young people interested in elections. In the classroom, as the students engage in the lesson, this pushes them to learn more about elections that occur. As students are better are understanding than memorizing what they are being taught, they become more interested in what is currently going on politically and keep up to date on information that is related to elections.

Teacher Pay: ‘A National Issue’?

Even with bonuses based on high student scores, teacher pay in Mississippi is still extremely low compared to teacher pay in other states. That changed somewhat thanks to the passage of the Start Act, which Gov. Tate Reeves signed into law in 2024, giving teachers a $5,000 average annual pay raise. Despite the passage of the Start Act, Mississippi still ranks 48th in the nation for teacher pay.

Teachers in Jackson say that this is still not enough. “Considering that we’re paid monthly it wasn’t a huge increase. It wasn’t much, and it wasn’t very significant, but I did appreciate it,” said Azaria Edwards, a teacher from Brinkley Middle School in Jackson. “From the perspective of my other colleagues, I don’t think the small raise was beneficial for them.”

Most teachers have a family to support and bills to pay—plus other expenses often for the classroom—which leaves them with little income for their needs.

Edwards’ colleagues emphasize that being a teacher is not their only priority, as they have personal lives and responsibilities outside their profession. “As far as bringing teachers into JPS, I feel like you got to (sic) come in to know what it is really about,” Edwards said. For her, it is not enough to simply observe or hear about it; you have to be directly involved to fully understand the situation.

“We have good benefits and things of that nature, but the pay could just be compared to outside districts and outside states,” Edwards said. While teachers acknowledge that y the Jackson Public School District provides benefits, they also believe that the pay should be comparable to other districts and states in order to retain and attract teachers.

“I have met a lot of teachers who feel that they are not supported in JPS, and I’ve learned that it is a national issue,” Edwards said. This lack of support can have a negative impact on teachers’ morale and ultimately affect the quality of education the teacher can provide.

Low Morale and Insufficient Support

If the quality of education teachers provide is affected due to low morale and insufficient support, it will ultimately affect the students’ learning experiences. “As a teacher, I see firsthand the significant impact that the teacher shortage has on our students,” Azaria Edwards says. “When teachers frequently take days off, whether for illness or other reasons, it really takes a toll on the kids. When they see that teachers are consistently missing it affects them deeply.”

This inconsistency disrupts their learning and academic performance. “They crave stability and reliability from their educators. The continuity of having the same teacher each day is vital for their educational success and overall well being,” Edwards said.

This continuity becomes even more critical in schools serving predominantly Black students, where the turnover rate for teachers is extremely high at almost 20% compared to just 12% in predominantly white school districts. The instability creates a high turnover rate that can lead to a cycle of underperformance, further diminishing the quality of education that students receive.

Edwards, who has worked in a predominantly Black district, acknowledges that people of different cultural backgrounds experience the same challenges despite different geographical locations. “I think we’re literally the same. We literally have the same issues, the same problems with our administrator, the same problems with parents, the same struggles with the students,” Edwards said.

Teachers’ pay is not the main issue causing the teachers to leave; racial discrimination and the generation curse could continue to affect successive generations of students and teachers. Many teachers or students are leaving the profession or district because of the unfairness throughout the education system. The issues discussed in the education system such as low teacher pay, racial discrimination,and the generational curse of educational inequity , are policy matters that impact the quality of education and retention of teachers . These issues are election focus points, as candidates often campaign on promises to address these issues through increased funding, equity initiatives , and educational reforms.

‘My Mama Always Taught Me to Defend Myself’

“Let my hair go. I’m not gonna say it again,” said 12-year-old Linda Ford, a short, brown-skinned girl with long black hair.

In 1970, schools in Mississippi had just begun to desegregate on the heels of a federal court order finally enforcing the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, and Ford was riding the bus to Hardy Middle School when a white girl kept pulling her hair while sitting on the seat behind her. She asked her multiple times to stop, but the girl kept going just to pick on her.

The middle-school victim was fed up and decided to take matters into her own hands, getting up and slapping the white girl behind her. They fought on the bus, and once the bus driver and a couple of other students broke it up, they were taken back to the school. Once they arrived, the consequences were severely different—even though they both did the same thing.

“My mama always told me to stand up for myself,” the now 66-year-old Ford says.

“TEACHER DEMOGRAPHICS AND STATISTICS IN THE US” says, in Mississippi, only 25% of teachers are Black. This stark difference in the racial makeup of Mississippi has deep roots, as Linda Ford remembers from her own experience at the newly integrated Hardy Middle School in Jackson, Miss.

At the time, Hardy Middle School was predominantly white before they had fled to suburan public schools and segregated academie to avoid integration. So white people normally had the upper hand when problems or fights occurred with students from the opposite race.

Once everyone was in the office and settled down, Ford told the principal what happened, and so did the other girl—truthfully, actually admitted her wrongdoing—but the result still didn’t end well for Ford. The young Black girl was expelled from school, while the white girl received no punishment, even though she was the one who initiated the conflict. Once she was expelled, Ford’s mom tried to get her back in school, but the supervisors and administration did not want to hear her arguments.

“I’ve seen similar situations like this at my grandbaby’s school,” said the now-grandmother. Fifty years on, schools that are predominantly white often still have racial discrimination often in more subtle ways:“What We Know About Teacher Race and Student Outcomes’’ states that Black students spend less time in the classroom due to discipline, which further hinders their access to a quality education. Black students are nearly two times as likely to be suspended without educational services as white students and are also 3.8 times as likely to receive one or more out-of-school suspensions as white students. In addition, Black children represent 19% of the nation’s preschool population, yet 47% of those receive more than one out-of-school suspension.

In comparison, white students represent 41% of preschool enrollment, but 28% of those receive more than one out-of-school suspension. Even more troubling, Black students are 2.3 times as likely to receive a referral to law enforcement or to be subjected to a school-related arrest than white students.

Taking away these learning opportunities from students could potentially cause inequities in classrooms and in life.

That leads to another concern in the upcoming elections.

Teaching and Understanding Critical Race Theory

In March 2022, Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves signed a bill prohibiting public schools from teaching critical race theory. Critical race theory is an academic construct used in higher education studies to analyze racism’s systemic impact on society, meaning that racism is embedded in American history in ways described in this article. This has caused different states to ban critical race theory from schools’ curricula, and has become a political talking point for conservative lawmakers, despite the fact that only one course among the thousands taught at Mississippi’s public colleges centers on critical race theory.

After Reeves signed this prohibition into law, Mississippi became the latest Republican-controlled state to legislate how history is taught. Bill author State Sen. Chris McDaniel, R-Ellisville, told CNN in February CRT promotes “victimhood” instead of student success.

“I think it’s important that parents also teach their children this information, but banning it in schools further silences the information and history,” said Jamian Rush, a local college professor. “You can see how race has affected black people socially and through politics. I think it’s something that’s important to teach. I don’t think it’s instilling victimhood; it’s just about teaching history.”

Courtesy Jamian RushJamian Rush, a local college professor, believes critical race theory should not be banned from education because that further silences the information and history.”

But white people opposed to CRT claim that it is a form of “reverse racism.” Rep. Ralph Norman, a South Carolina Republican, said at a news conference: “Critical race theory asserts that people with white skin are inherently racist, not because of their actions, words or what they actually believe in their heart—but by virtue of the color of their skin.” Rep. Lauren Boebert, a Colorado Republican, added: “Democrats want to teach our children to hate each other.”

Nakisha Davis, a local school administrator, says those politicians are trying to slander critical race theory, which is harmful. “I do think politicians should stand up and discuss it more, but then again it’s scary because other politicians might use it to a disadvantage,” she says. “What we’ve gone through in the past is necessary to discuss for reflection and improvement, but anything other than that shouldn’t be talked about in a negative light.”

Davis says everything African Americans have worked so hard for is being stripped away. “You can open any textbook and see all these white historical figures, but when it comes down to the history of African Americans, you want to strip it from us. How fair is that?” Davis asks.