By Kierra Rand

Mississippi State Sen. Bradford Blackmon, a Democrat representing District 21, rose to his position without even taking a civics class in high school. Blackmon attended the private and well-regarded St. Andrew’s Episcopal School, which still did not offer a civics class at the time.

When Blackmon was in high school, he was not conflicted about the lack of a civics course, but after graduated in 2007, he attended the University of Pennsylvania for undergrad and then University of Mississippi for law school. When he took government classes during that time, Blackmon thought to himself: “This is how it works. I wish I had known about this before I got to this point.” After having these experiences, he feels upset about people his own age—and people younger and older—not being educated on the election and political process.

Understanding the U.S. electoral system is crucial to being an educated, and engaged, voter. “Civic education empowers us to be well-informed,” The Importance of Education states. “It is a vital part of any democracy and equips ordinary people with knowledge about our democracy and our Constitution.”

But in Mississippi, only 0.5 credits for taking “government” classes are required to graduate from high school. And that is often not from a civics class.

“Young people who recalled high-quality civic education experiences in school were more likely to vote, to form political opinions, to know campaign issues, and to know general facts about the U.S. political system,” Tuft University’s Center for Information and Research on Civil Learning and Engagement, or CIRCLE, reports.

In the lead-up to the 2024 presidential election, some people could be confused, for instance, about which of the three branches of government perform certain functions, with come criticizing the Joe Biden administration for the fall of Roe v. Wade. However, the U.S. Supreme Court, and especially justices appointed by former President Donald Trump, made the decision to overturn Roe vs. Wade, ending reproductive autonomy for many American women.

Voters cannot be blamed for buying into such misinformation, Blackmon said. “It’s not their fault because they were never offered the education,” Blackmon said. “So I don’t blame them for being uninformed. But we just have to find a better way to inform them.”

The Confusion of the Electoral College

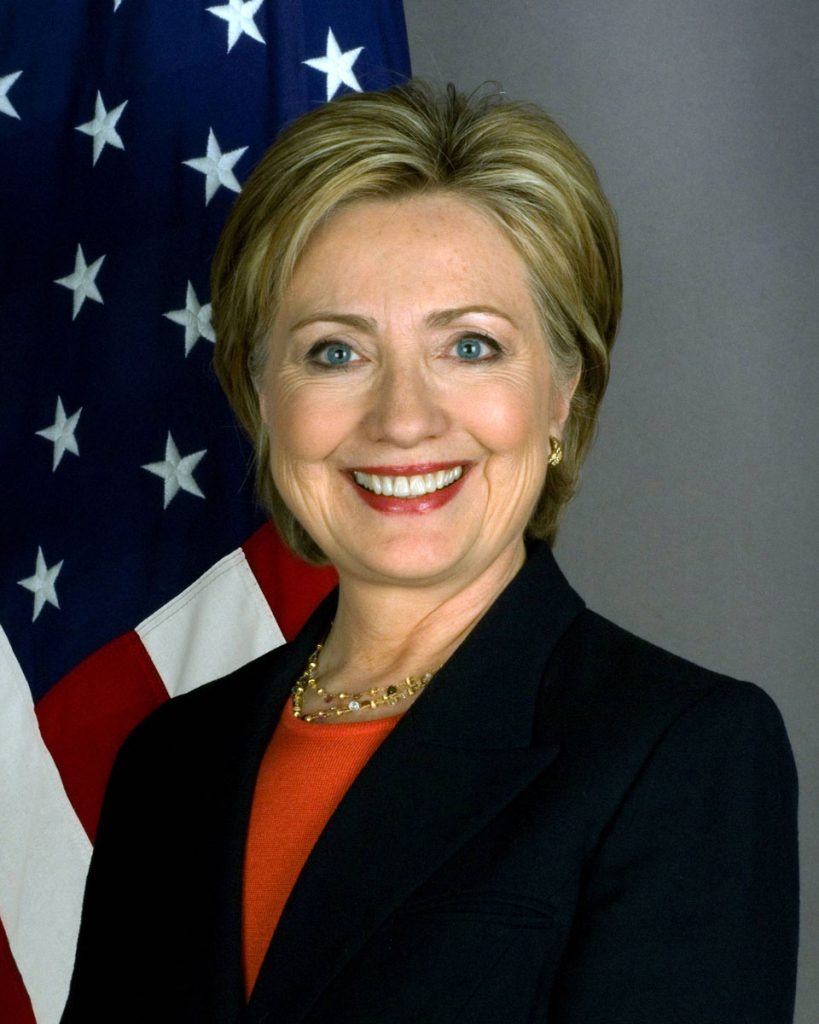

The way a president is elected can also easily confuse someone who has not studied the electoral college. The candidate who wins the popular vote—like Hillary Clinton did in the 2016 election over Donald Trump and like Al Gore did in 2000 over George W. Bush—is not guaranteed to be the person who becomes the president. The electoral college is a faction of 538 electors who meet to cast votes for the president and vice president. The number of electors is derived from how many members of Congress each individual state has. Each state has two senators, and one elector is allotted for each member of the House of Representatives. Electoral votes are awarded on the basis of the popular vote inside each state.

That means the election of an U.S. president comes after a long series of events, which does indeed begin with the vote of the general public. First, citizens’ votes are counted in a statewide tally. Next, the electoral college will vote. Most of the states have a system that dictates that whichever presidential candidate wins the popular vote in a state will be granted all electoral votes assigned to that state. This system excludes Maine and Nebraska, which apply a “proportional representation” system and thus split electoral votes depending on the popular vote spread.

The winning presidential candidate needs to have at least 270 electoral votes—which is more than half of the electors—to win the election. Lastly, all the members of Congress officially certify the electoral votes.

This system is why in a state like Mississippi a presidential candidate may draw 554,662 votes—as Barack Obama did in 2008 against John McCain’s 724,597 votes—but none of them counted toward the overall electoral college. In that case, it didn’t affect the outcome of the election, as Obama drew the most electoral votes across states considered “blue” because they vote mostly for Democrats versus “red” states that lean toward Republicans.

This also means that candidates and campaigns do not spend much time and money in states that are considered “safe” states for one or the other party, electing to inundate “toss-up” states—today, often in the midwest—with volunteers, campaign ads and mailers.

Unlike in presidential elections, elections of state officials are based on the popular vote. Citizens are customarily more in contact with their state and local government officials. As voters choose state and local officials, their wishes can have a heavy impact on local legislation. That means it is easier for citizens to be heard on local levels due to the elected officials being closer to them geographically.

“This starts on the local level because they are more able to talk to the citizens right then and there,” Blackmon said. “The citizens can reach out and tell us about the things they need in the community.”

Kierra Rand is a 2024 Youth Media Project student who attends Jim Hill High School.